Twenty summers ago, my mother passed away. I was her primary carer. She had always dreamed of visiting Canada but never made it, so I went on her behalf. Although D.H. Lawrence never visited Canada, it was a significant ‘unknown’ place in his writing as it is mentioned in his first novel, The White Peacock (1911) as a place of hope “where work is strenuous, but not life; where the plains are wide, and one is not lapped in a soft valley, like an apple that falls in a secluded orchard.”[i] It is also where Constance Chatterley and Oliver Mellors consider eloping to at the end of Lawrence’s last and most infamous novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928)[ii].

On my return from Canada, I moved to Little Eaton with my then girlfriend and got some work tarmacking with a company a few doors away. It was hard work, but probably the most enjoyable job I’ve ever done in terms of camaraderie. In May, I returned to give a talk to the Little Eaton Local History Society in my current capacity as a Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Nottingham Trent University.

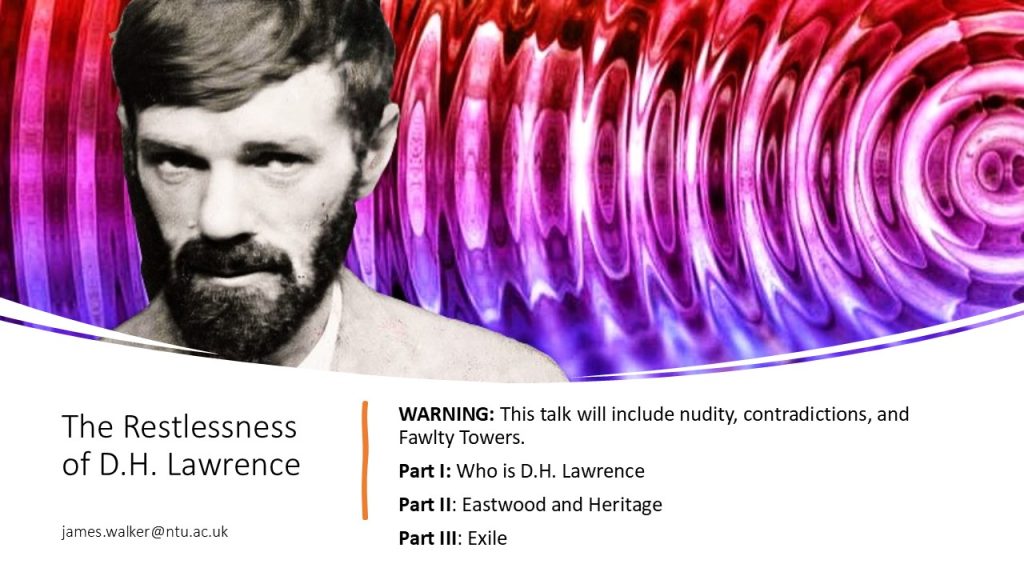

I began the talk with reference to Ken Dodd, explaining how he got banned from a theatre in Nottingham because he refused to get off stage. He loved performing gags and didn’t care a hoot whether people caught the last bus or not. It’s a bit like that with Lawrence. There’s so much about him that you don’t know where to start and when to end. For example, in the 24hrs before my talk there had been 16,100 files uploaded to Google about the bearded one. A quick search of Google scholar revealed 2,500,100 references. Therefore, I am always keen to emphasize that, like Manuel in Fawlty Towers, I know nothing.

What I do know about Lawrence is he escaped a mining village, travelled the world, and possessed that most important of human characteristics – curiosity. For these reasons alone I could talk about him forever but cut my talk short of the 2hr mark before a couple of snoozers started snoring.

I enjoy talking about Lawrence because he constantly prods you in the ribs and keeps you on your toes. No subject was off bounds. More importantly, he didn’t want to just know about the world he wanted to connect to it which is why he lived such a restless life. As his wife Frieda wrote in her memoir Not I, but the Wind

‘To me his relationship, his bond with everything in creation was so amazing, no preconceived ideas, just a meeting between him a creature, a tree, a cloud, anything. I called it love, but it was something else – Bejahung in German, ‘saying yes.’’[iii]

The talk was in three parts, covering a potted history of his life, home and heritage, and his self-imposed exile – with various quotes and asides thrown in along the journey. You’re always meandering with Lawrence. He sways you from side to side. He doesn’t do linear.

But the most important task on such evenings is to get people reading. I love his letters the most because of his acerbic wit and so would make any of the eight volumes of his Collected Letters my first port of call. If you want a sneak preview, watch one of my monthly Locating Lawrence video essays on YouTube. In terms of novels, you can’t go wrong with The Rainbow or Sons and Lovers. John Worthen’s The Life of an Outsider is a very user-friendly biography for those wanting an overview of his life and how it shaped his writing. In terms of contemporary fiction inspired by Lawrencian mythology, try Alison MacLeod’s Tenderness or Rachel Cusk’s Second Place. Whereas Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage is probably my favourite book of all time and gets better the more familiar you become with Lawrence.

To join the D.H. Lawrence Society and enjoy monthly talks, an annual festival, and a free copy of the Journal of D.H. Lawrence Studies, visit the website here. To join the Little Eaton Local History Society visit here.

If you would like me to give a talk on Lawrence, get in contact.

[i] D. H. Lawrence, The White Peacock, with a Preface by Harry T. Moore (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1966), 67

[ii] For more on these points see see Evelyn Hinz ‘D. H. Lawrence and “Something Called ‘Canada’”’ Dalhousie Review, Vol 54 (2), 1974

[iii] Frieda Lawrence, Not I, But the Wind… (Delphi Classics, 2017)