For the past year I’ve been working with Loretta Trickett on research for The Bigger Picture which explores the impact of intergenerational arts programming on the experiences of exclusion and isolation within minority communities in Nottingham. This is a multi-collaborative project that includes researchers at the University of Nottingham, Nottingham Trent University and Bright Ideas Nottingham. Together we have been looking at cultural institutions such as National Justice Museum, New Art Exchange, and Nottingham Contemporary as well as many others.

Loretta has held focus groups with various retired people to try to identify possible barriers to the arts and how local organisations can make themselves more inclusive and accessible. Her research has found strong correlations between the arts and health and mental wellbeing. A lot of the retired people she interviewed stated that the arts fill an essential gap in retirement by essentially providing stimulation and building community. One interviewee talked of the arts being a ‘cultural trigger’ that led to obsessive behaviour. He stated that being intrigued by a painter could lead to him reading books about the artist, visiting countries related to the artist, or learning to paint himself. Other people talked about having no time during their working lives to pursue personal goals and then being busier in retirement than they were at work. Over and over again the research reinforced how important the arts were to individuals on numerous levels, not least in providing a sense of self now that work no longer defined their identity.

My role in the project has been finding ways of disseminating the research so that it’s more accessible. This was done through a visual narrative and a graphic novel.

The visual narrative was created by Paul Fillingham, Richard Weare and me. This 35-minute film condenses hours of focus group meetings. The aim was to find recurring themes and categorise experiences so that viewers could get an overall feeling of how the retired felt.

I like the idea of a continuous multi-authored narrative and first got the idea when I worked at LeftLion magazine. The editor at the time, Al Needham, wanted to tell Nottingham’s version of Hillsborough but was cautious given the sensitive nature of the subject matter. The best way to do this was to piece together first-person experiences in one article, thereby allowing self-representation. Two years ago, I helped put together a similar project for the East Midlands Heritage Awards whereby Richard Weare and me conducted interviews with heritage professionals and then sutured these Vox Pops together to create Heritage Confessions.

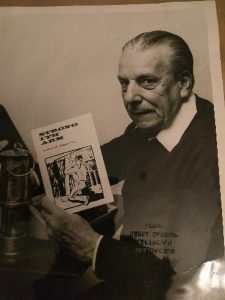

Photograph Aly Stoneman

The graphic novel is for Whatever People Say I Am, the follow-on project to Dawn of the Unread. I held writing workshops with a group of retired people and together we identified key issues they faced on retirement. I then gave them a series of questions (‘what do you miss most about work?’ ‘what is the most important thing to you in retirement?’ etc) and compared their responses to try to narrow down themes and find common patterns. Then we worked on a narrative arc and eventually produced a multi-authored script. This was really important as it enabled the focus group to create something tangible and experience the joys (and frustrations) of writing a script rather than having one imposed on them. If they enjoyed this process, hopefully they would carry on writing…

The script is currently being illustrated by John Brick Clark. Brick is retired (born in 1949) so he was the most appropriate artist for the commission. John was one of our previously commissioned artists for Dawn of the Unread. I don’t want to give anything away, so keep your eyes on the Whatever People Say I Am website. Our aim is to publish this first story for April.

I’m also working on another story for this project about a care home. It involves a Lancaster bomber pilot, a woman with a male horse called Princess, and an 87 year-old taxi driver from London who read his first poetry at 86. More of this in another blog…

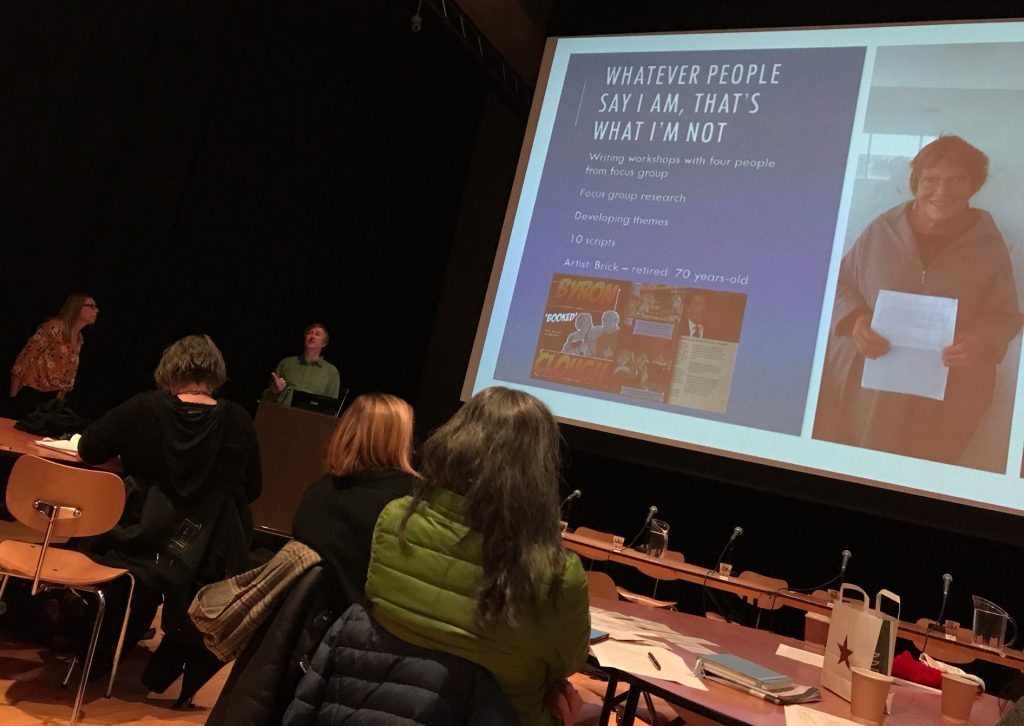

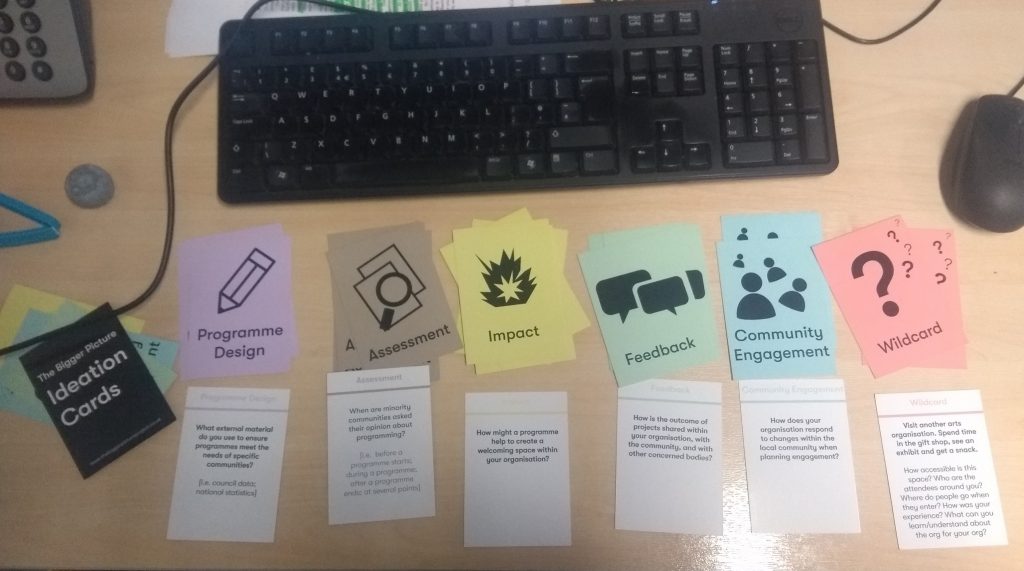

Photograph James Walker. Ideation cards created by Karen Salt and her team

On Friday 1 February Loretta and me presented our findings at the Nottingham Contemporary in what was one of the most enjoyable conferences I’ve ever been to. Karen Salt (University of Nottingham) produced a pack of cards that ask various questions and enable arts organisations to understand their aims and objectives in relation to participation. These act as triggers for critical conversations, and had everyone talking in a way that wouldn’t usually happen in a conference.

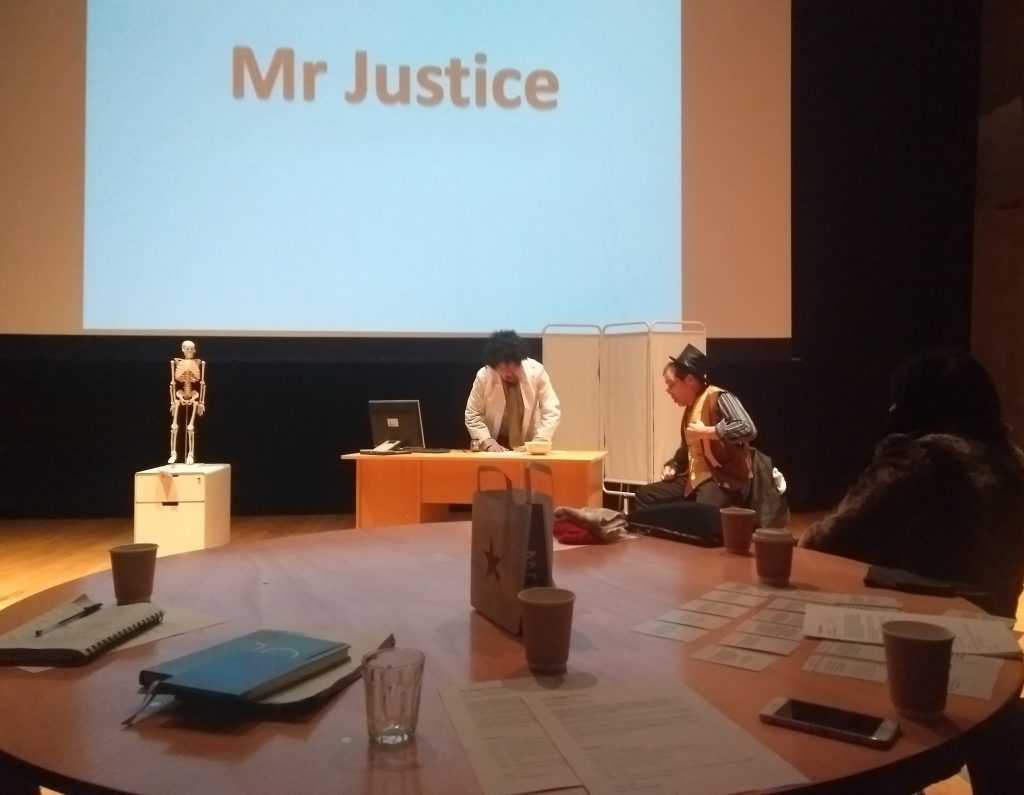

Bright Ideas, led by Lisa Robinson, took feedback to another level, putting on a performance in which arts organisations were asked to take a health check. The play was performed by a community of researchers who had not met prior to the project and was funny, inciteful and clever. They addressed some difficult issues in a very thoughtful way and I’m sure the organisations in question learned a lot more about their practice than they would from the dreaded feedback form.

Photograph James Walker. Mr Justice is prescribed some radical surgery…

Too often academic research is cold, stale and so far up its own arse it (insert witty comment here). This led Geoff Dyer, in Out of Sheer Rage, to conclude of academic criticism that it kills everything it touches. ‘Walk around a university campus and there is an almost palpable smell of death about the place because hundreds of academics are busy killing everything they touch.’ This was not the case on Friday. Together, we produced some innovative and engaging approaches to research that were fun, informative and accessible.

The Bigger Picture is a collaboration between Nottingham Contemporary, New Art Exchange, National Justice Museum, Bright Ideas Nottingham, University of Nottingham, Nottingham Trent University and Midlands4Cities. Funded by Arts Council England. Nottingham Contemporary’s public programme is jointly funded by Nottingham Trent University and The University of Nottingham.