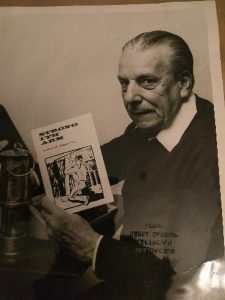

Photo of photo by James Walker.

Narratives of coalmining have tended to focus on the lives of men from the North East, Yorkshire, and Wales. But thanks to the work of Natalie Braber and David Amos, the history of the East Midlands is starting to be recognised. It was through their research that I came across the pit poet Owen Watson, who plied his trade at Heanor.

Heanor colliery started off mining for shallow coal, then when this ran out they sunk bell pits. This was particularly dangerous as coal had to be got out sharpish before the pit sides collapsed. When they needed to go deeper underground, engineering was required. Shafts, horse gins, and other structures were erected, with headgears and engine houses following soon after. Iron and steel industries began to develop to support these needs. Work was plentiful, communities developed, British history was written. But industrial developments were pricey which meant big organisations and wealthy families stepped in and took over during the 19th century. In Heanor, mining operations were dominated by the Butterley Company and the Shipley Collieries.

If we skip forward a century, the Coal Industry (Nationalisation) Act in 1946 established the National Coal Board. This was responsible for underground mining and later, opencast mining. Despite developments in mechanisation and the sinking of new collieries, the industry was doomed, unable to compete with oil, gas and nuclear power. As the Heanor area was a very old coalfield, it wasn’t long before local pits got shafted. New Langley Colliery was closed in 1960 and Ormonde followed on 25 September, 1970 – despite employing 1219 miners in 1963, who collectively were turning out 4200 tonnes a day. With it went a whole way of life, as well as community.

In a recent documentary for BBC Radio 4 called Tongue and Talk: The Dialect Poets, I chatted to Bill Kerry III who has updated Watson’s poem Wheer are t’ gooin’ when Ormonde shuts? into a folk song. The poem was originally published in Strong I’th’ Arm – The Rhymes of a Marlpool Miner (1975) and captures the uncertainty and optimism that miners felt as pits closed and they were forced to try and find work elsewhere, as captured in the opening three stanzas below.

Wheer are t’gooin’ when Ormonde shuts?/You hear where e’re you go -/Ah have na’ made me mind up yit!/Ah have na’ exed ah Flo!

Ah’m thinkin’ o’ gooin’ t’ Babbin’ton!/ What abert Moorgreen?/ Ah know they anna’ long t’ goo -/Tha’ knows pal, what ah mean.

It doesna’ matter wheer tha’ goos/Tha’ll ‘ay t’ flit agen/But it tha’ goos a long wee off/What abert your Gwen?”

As a result of the programme Owen Watson has been added to John Goodridge’s database of working class poets. This means his work will be read by future generations. I’m particularly proud of this as there’s no point doing projects unless they have genuine impact. But the real highlight was being contacted by Watson’s grandson Richard Buxton shortly after the broadcast. We met up for a cuppa and he told me more about his talented grandfather.

Watson was a quiet, serious man. Richard was seven when Watson died in 1980 but he had vivid memories of walks with him on a Sunday afternoon around Shipley Park. Watson lived opposite Shipley Park on Roper Avenue in Marlpool. “We used to walk around Osboune’s Pond, up to Mapperley Reservoir then into the woods around the old Shipley Hall, where he would show us the gravestones of the Squire’s dogs buried in what would have been the grounds. All the while, he would be pointing out different mushrooms and toadstools, what you could eat, and what you couldn’t and asking me to listen to the sounds of the natural world and telling me which bird was responsible for which song. He’d often break off a sprig of Hawthorn and give it me to chew, saying it was better than bread and cheese.”

The love of nature is a familiar theme among miners, presumably because they spent most of their lives in darkness in the bowels of the earth. This is epitomised by the work of DH Lawrence whose novels are crammed with references to nature and names of flowers, many of which he learned through walks with his father who worked at Brinsley Colliery in Eastwood.

These walks clearly had a profound effect on Richard. “I credit him with sparking my interest in the natural world and birds in particular. I work for the city council but my dream job would be working for a Wildlife Trust or the RSPB. I’ll always be thankful to him for this. He was a great naturalist and artist and I’m sure that my love of natural history comes from our walks in the countryside at a formative age. He was an expert at identifying bird song and seemed to me to have an encyclopaedic knowledge of the natural world.”

Miners could be a rough lot, but many were incredibly creative too. Art, poetry and music offered an escape from monotonous labour, as well as a means of coping with the constant threat of death. Owen Watson was also a gifted artist and his grandson remembers him helping him draw a picture which was shown on Midlands Today (they used to show artwork that people sent in before the weather forecast).

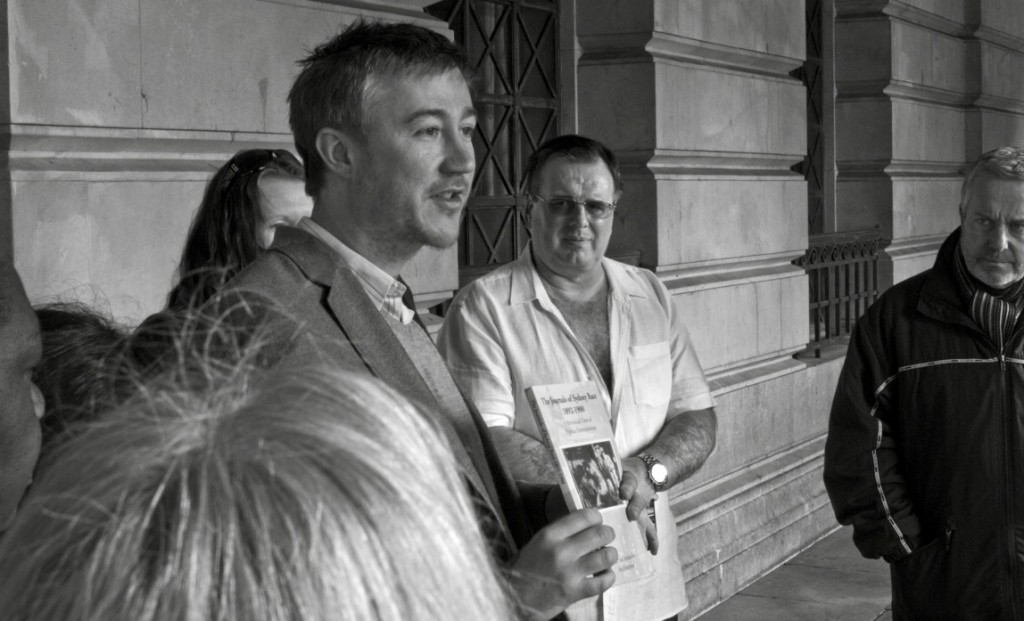

To celebrate Owen Watson’s life and work there’s a literary walk planned that will start at Eastwood library. On this we’ll be retracing his walk to work and reading his poems along the way. It’s being led by David Amos and will include some of the updated folk songs as well. Please see the mining heritage website for updates or David’s Twitter profile

The walk will start at Eastwood Library, Wellington Pl, Eastwood, Nottingham NG16 3GB.