Upside Down at the Bottom of the World is an award-winning play that details D.H. Lawrence’s brief spell in Cornwall and Australia. It has particular resonance for David Faulkner as he played Lawrence in the original play at the beginning of his career and has now directed it in his retirement.

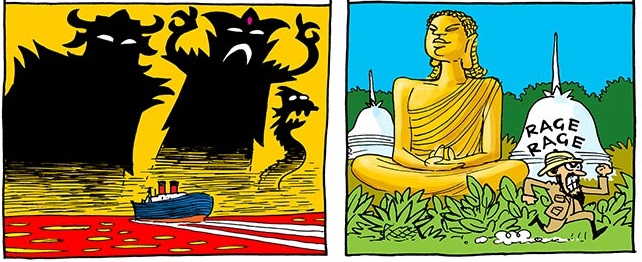

D.H. Lawrence lived in Cornwall from 30 December 1915 to 15 October 1917 in what he hoped would be a new life away from the industrial Midlands of his birth. It didn’t quite work out as he planned. He was accused of being a spy, his passport was removed, and he was booted out of Cornwall under the Defence of the Realm Act. His short tenure on the edge of Britain would have a profound effect on his ideas, not least his developing fascination with cosmic vibrations and the mysterious secrets of primitive cultures emanating from the dark black granite Zennor coastline.

Lawrence courted controversy throughout his short life, which is what I love most about him. He married a German woman called Frieda Weekley, a distant relation of the ‘Red Baron’, 15 days before the outbreak of WWI. The Rainbow, published the following year, lasted two months in print before being seized under the 1857 Obscene Publications Act. Prosecutor Herbert Musket declared it ‘a mass of obscenity of thought, idea, and action’ for daring to question fundamentals of everyday life, such as work, marriage and religion. Judge Sir John Dickinson ruled that the book ‘had no right to exist in the wind of war’, and that Lawrence was in effect mocking the very principles British men were fighting to defend. With no sense of irony, copies of The Rainbow were publicly burned, while ‘our’ boys fought for freedom on the Western Front.

Lawrence would live a restless life, travelling the globe and staying no longer than two years in any one place. His experiences of living in Cornwall and Australia would serve as the backdrop to David Allen’s play Upside Down at the Bottom of the World. Originally performed in 1980, it scooped the Australian Writers’ Guild Award for Best Play. More recently, the play has been revived by David Faulkner and was performed at Lane Theatre, Newquay in March. It’s hoped the play may make its way back to Nottinghamshire at some point.

David Faulkner: Photo Carolyn Oakley

Frieda once said that what she loved most about Lawrence was his saying ‘yes’ to life, known as ‘Bejahung’ in German. The same could be said of David Faulkner. “One day, while on the London tube, I happened to see an advert in Time Out which read, ‘English Speaking Actors wanted for the Cafe Theatre Frankfurt’. Rather than send my CV, photograph and covering letter, I bought a £17.50 Magic Bus Ticket, packed an overnight bag and the next thing I knew I was in Frankfurt looking for The Cafe Theatre. Probably due to bare faced cheek rather than my chosen audition pieces I was offered the job. Eighteen months later I was still working at the Cafe theatre as both an actor and director, doing three monthly rep.”

It was here that he first encountered Davis Allen’s play, offering to play the part of Lawrence after the original cast member had to withdraw. “I had just ten days to learn the lines and replicate the role in preparation for a continued three-month tour of Holland and Germany. I remember so little of that production but often returned to the script with the thought that one day I would revive it.”

Now he has found himself directing the play that helped kickstart his career. Although remaining true to the original script, David has introduced some interesting extra details, such as Lawrence knitting bloomers. “Frieda liked wearing French knickers yet Lawrence preferred her to wear bloomers, which he often made for her. Therefore, at the beginning of the play we see Lawrence sewing a pair of bloomers which Frieda puts on in front of him. We see this sexual game playing is indeed a significant part of their relationship.”

Photograph: Carolyn Oakley

David is now retired and living in Cornwall and runs a small touring company as well as guest directing for several local community groups. So why did he decided to put the play on now? “Sometimes a play comes along that has particular relevance at a certain time. Upside Down at the Bottom of the World is one of those plays. The political turmoil of the Diggers, the right/left struggle, the influence of the Unions in conflict with the capitalists is almost a mirror to what we are experiencing here and now.”

Brexit has certainly delivered plenty of turmoil as of late, so would Lawrence have voted ‘leave’ or ‘remain’? “Now that’s a hard one. Married to a German, he may have voted Remain. Then again having no truck with a capitalist world order, and being the son of a miner, perhaps, Leave. Now that would make a great play, haha.”

Upside Down at the Bottom of the World was performed at Lane Theatre, Newquay, Cornwall, TR8 4PX from 14-16 March and 21 – 23 March 2019. This blog was originally published on the UNESCO City of Literature website. I’m currently working with Paul Fillingham on the D.H. Lawrence Memory Theatre. You can learn more about this digital pilgrimage by following the project blog or Instagram account.