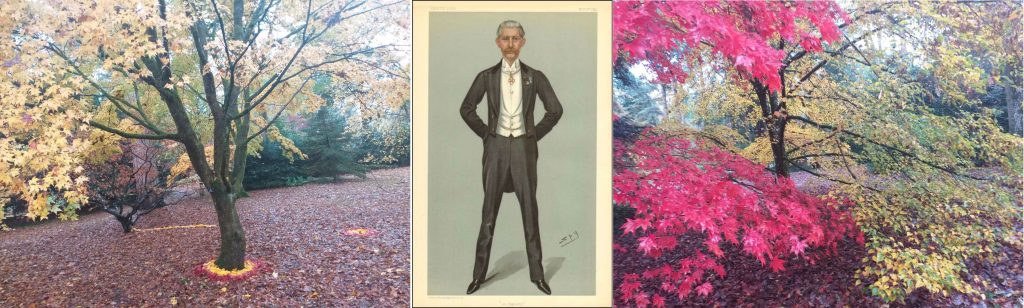

Photos by James Walker. Picture of Sir George published in Vanity Fair 16 November 1899.

When Sir George Lindsay Holford (1860–1926) inherited Westonbirt House, he set about continuing his father’s work in developing the Westonbirt Arboretum. He did a magnificent job, with the site handed over to the Forestry Commission in 1956 and Forestry England in 2019. It is now known as the National Arboretum and consists of over 18,000 trees and shrubs, over 600 acres.

Sir George also inherited Dorchester House in London, home to an impressive art and book collection. But he wasn’t much of a reader and so spent most of his time at Westonbirt. An article in The Times from 1926 states:

“He was indeed, one of the most successful amateur gardeners of the time, and though famous as a grower of orchids, amaryllids and Javanese rhododendrons, his garden and estate show a wide catholicity of taste. The arrangement of the many rare and exotic trees there and the skilful use of evergreen species as background and to provide the shelter so needful in a cold district like the Cotswolds, have rarely been equalled; there is no crowding of the trees; each is able to show its true form and all have been well cared for. On few estates has the autumnal colouring of deciduous trees been so cleverly used by harmony and contrast, as, for instance, in the planting of Norway maples and glaucous Atlantic cedars.”

I love trees and books, so I’m a bit jealous of Sir George. But I’m dedicating this blog post to him because he once held a ‘colour party’ picnic in his Acer glade. I’m sick of hearing about, to borrow from D.H. Lawrence, ‘ugliness, ugliness, ugliness’ whenever I switch on the radio or open a paper as the Brexit Party dominates the national conversation. So, in homage to Sir George, I’m proposing a colour party. To get involved, just run to the woods and enjoy autumn colours. I think everyone should do this before voting. And instead of focusing in on boundaries and borders, think instead of how such ‘mechanical thinking’ (another Lawrencian phrase) has led to the absolute destruction of the natural world and its resources and the ushering in of the Anthropocene.

Photo by James Walker.

Robert Macfarlane, who writes eloquently about these issues, helped to raise awareness of the Sheffield tree protests in 2013 when a Private Finance Initiative contract set up by the council nearly led to 17,000 trees to be felled in a cost saving exercise that would have removed colour from leafy suburbs across the steel city. Now more than ever we need to have colour parties; to stand under trees in the rain and listen to how different leaves create different tempos with the downpour; to bestow trees with legal rights – for it’s not just colour they provide but the oxygen that we breath. The one thing we don’t need is to fixate on the parochial jingoism of the millionaire Nigel Farage, son of a stockbroker.