Photo by Paul Fillingham.

A digital storyteller is someone who makes content available across media devices. This could be videos on a Youtube channel, an App that gets you to perform tasks, or via a website. The content usually has an interactive element to it, meaning that the reader, or perhaps more accurately the user, needs to engage with the story in some capacity.

Whether we like it or not, reading has changed. Younger audiences now expect content to be presented in a wide variety of formats and in bytesize chunks. They read on their mobile phones, their iPads and those laptops that get smaller and lighter each year. To accommodate these changes my digital projects conform to a simple ethos: If the 20th century was about knowledge, then the 21st century is about experience. Therefore I’m always looking at ways to bring people into the conversation.

My specialism is in cultural heritage trails, exploring the lives of key Nottingham writers. I do this in collaboration with Paul Fillingham, of digital agency Think Amigo. Our first project together was The Sillitoe Trail (www.sillitoetrail.com) which explored the enduring relevance of Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Very simply, this was an App which navigated you via GPS to key locations of the novel. At each location you would be provided with pictures, facts, quotes, audio and an essay. These in turn were created by different artists. My aim was to make literature more accessible by providing different ways of understanding the story, with the hope that our readers may then go on to read the book. More recently we created Dawn of the Unread, an online graphic novel serial celebrating’s Nottingham’s literary history.

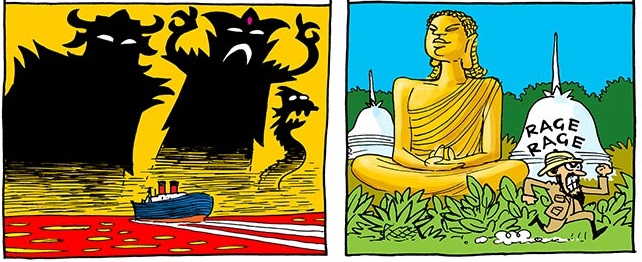

Taken from Dawn of the Unread

Now Paul and I have turned our attention to D.H Lawrence. Lawrence was a controversial writer who championed sensuality in an over-intellectualised world. In the 1920s he embarked on a journey of self-discovery known as his ‘Savage Pilgrimage’ which took him across Europe, Asia, Australia and Mexico. Accompanying him on his journey was a travel-trunk, which we encountered at the recently closed down Durban House, Eastwood. We were intrigued by the object, its construction, its floral decoration and internal drawers; which in addition to housing Lawrence’s socks and undergarments would have contained manuscripts, sketches and stories, documenting his travels around the globe.

We want to develop Lawrence’s personalised travel-trunk as a Memory Theatre. Memory Theatres, very simply, were filled with rare and expensive artefacts and once used by the aristocracy to convey cultural capital and status. But whereas only selected guests got to view them, ours will be available to all.

Photo taken at Birthplace Museum.

Lawrence lived a nomadic existence, travelling the world in search of Rananim – a utopian community of like-minded people. But he would never find it. In essence, he enjoyed the journey, rather than the final destination. In the opening chapter to Sea and Sardinia he talks of a desire that “comes over one” that is an “absolute necessity to move. And what is more, to move in some particular direction.” Rather than writing yet another book on Lawrence we want to capture this unsettled aspect of his personality by creating a moveable object.

Our Memory Theatre will be a beautifully crafted work of art in its own right, to be explored and admired, stopping off at key locations in Lawrence’s life. The drawers will contain artefacts that capture the essence of his personality. So for example, in 1918 Lawrence sent Catherine Carswell a shoebox containing 20 varieties of wild flowers with their roots intact, all carefully placed inside damp moss. In her biography of Lawrence she explains “With my box of Derbyshire flowers there was a small floral guide, written by Lawrence, describing each plant and making me see how they had been before he picked them for me, in what sorts of places and manner and profusion they had grown, and even how they varied in the different countrysides.” One of our drawers will contain a book of 20 pressings of flowers from Derbyshire. When the Memory Theatre arrives in Sardinia we will arrange for a local guide to add 20 more, and so on. As the Memory Theatre travels in physical and digital form, its aesthetic and emotional value will grow, accumulating its own savage history and provenance.

The Memory Theatre will include digital screens to give context to the artefacts. It will also have a virtual presence for those unable to see it in the flesh. Users will be able to virtually ‘open’ drawers with content geared towards the capture and sharing of the users’ experience.

The internet is all about collaboration, and at times it can bring the best out of people. If nobody uploaded videos, shared knowledge on Wikipedia, or stopped tweeting their opinions it would effectively be a technological void. I wonder whether Lawrence would approve. He was always seeking a small community of like-minded people. He certainly wanted followers. But I doubt he would approve. If he thought industrialisation dehumanised people, goodness knows what he’d make of the Youtube Generation, all gawping into screens.

I’d like to think of our D.H Lawrence memory theatre as a form of digital literary criticism in that we’re trying to create an artefact to represent and encompass the personality and body of work of a prolific writer. I want our students to look differently at stories, and the modes through which they can be told. Lawrence raged his way across the globe, his work was constantly censored, he wrote about sex, pit villages, he knew every flower off by heart, he was a prude, prickly, the greatest DIYer the literary world has ever know, he deplored money but was fastidious with it, and he had some very weird ideas about submission. How do we make this artefact look, smell and feel like Lawrence?

Photo by James Walker.

To help Paul and I think through the project, we’re working with three students from NTU for one year. Rebecca Provines, Richard Weare and Stephen Tomlinson are helping us think about the artefacts, reading and researching through Lawrence’s work, and figuring out costings and audience engagement. Then we’ll start to build it and map out our journey.

If you want to follow the progress of our digital savage pilgrimage then please visit our website. Lawrence was an avid letter writer and we’re paying homage to this by sharing our progress in a weekly blog. Better still, why don’t you leave a comment and join in the conversation?

This article was originally published in the Southwell Folio, November 2016.