If somebody had a look at my search history, they may conclude I’m a cock-obsessed fetishist. This is because for the past month I’ve been googling every iteration imaginable for penis: ‘Penis shaped bridge,’ ‘penis rainbow,’ ‘building that looks like a cock,’ ‘plants that look like a willy.’ It’s amazing what lurks deep inside the digital void. There’s something for everyone.

As it happens, my intentions are honourable. I’ve been researching for the third artefact in the D.H. Lawrence Memory Theatre: Phallic Tenderness. This was submitted by Stephen Alexander, author of Torpedo the Ark. Stephen is a writer who I greatly admire. He is provocative and playful. He is also a writer whose opinions I often disagree with.

Lawrence was a tad obsessed with his todger – but not in a puerile way (although in his younger days he did write a gushing poem about the magnificence of his erection). The phallus had symbolic meaning for him and represented a broad range of ideas that tapped into his life philosophy and belief in blood consciousness. If you want to know how, you’ll have to read Stephen’s pithy and provocative fragments.

There’s 12 of them in total – one for each hour – because I originally wanted to have a ‘Speaking Cock’. The clock would have a penis as an hour handle and visitors would press a button and it would spin round and land on an hour and one of Stephen’s essays would be read out. I even went as far as contacting one of my friends – a woman of Flemish descent – to see if she would like to read out some essays about willies. She never responded.

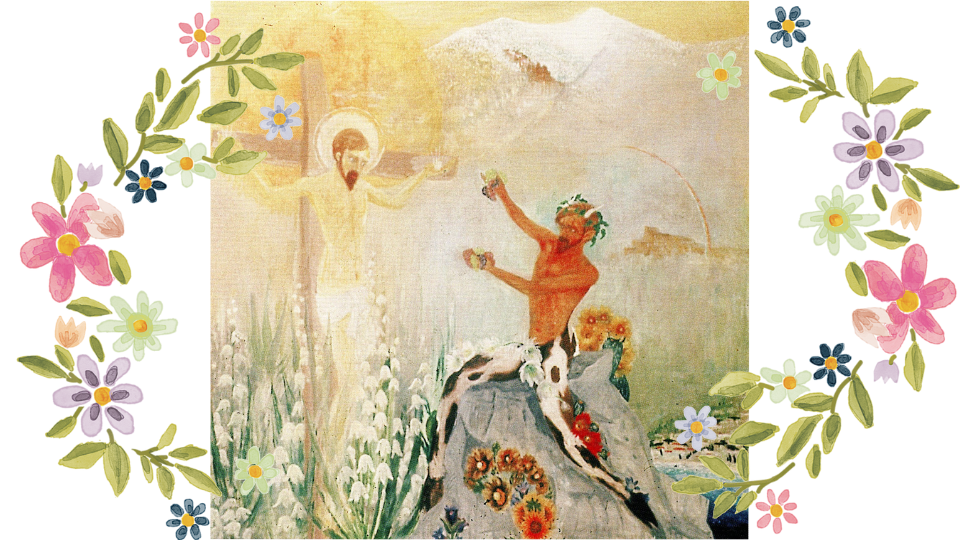

D.H. Lawrence as Christ by Dorothy Brett with an added flower border.

I decided against the Speaking Cock because it may lead our project to be perceived as a ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’ – a series of oddities to be gawped at and amused by – rather than a thoughtfully curated moveseum that explores key themes in Lawrence’s writing via artefacts. It may also have made light of what is a key philosophical strand to Lawrence’s writing, thereby defeating the purpose of its inclusion.

So how do you represent something as abstract as ‘Phallic Tenderness’ without turning it into a Carry On movie? My solution was to create a hybrid of the phallus and the phoenix to emphasise the transformative potential of this symbol rather than reduce it to an innuendo. I then added a flower border (for nature and tenderness) – and added a fringe filter in Pixlr to distort the colours and reinforce the transformative element. I think it works well, but I would. If you disagree, please get in contact.

I was thinking Mount Rushmore when I put these stencils of Oscar Wilde, Lord Byron and Marcel Proust together. This was the holding image for an essay on falsifying phallic consciousness.

Likewise, I needed holding images for the 12 fragments. These had to be strong pictures that captured the essence of each article while luring readers in. Given Stephen explores the phallus in terms of consciousness, power, union, Christ and gynaecological deconstruction, it is little wonder my Google search history was so weird.

The two previous artefacts in the memory theatre comprised of four essays. As this one included twelve (because they were originally intended to form a clock) it would have looked like we’d gone willy mad if I’d populated it with twelve phallic images. Thus it took a long time to design appropriate images.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that I visited Stephen in Hackney in 2018 when I had the original idea for a speaking cock. His essays have sat patiently in my inbox for five years. Part of the reason for the delay has been Paul, my co-producer on the project, has been too busy to upload content to the website as he is involved in various projects while also running his business, Think Amigo. We have found a compromise and he has redesigned the website so that it has a WordPress interface. This means that I can now upload essays and help with the design. I can only compare this with being given control of the S.S. Enterprise and feel as if I have the entire galaxy at my fingertips.

Over the past five years I have learned so many new skills from video production (the above video took two days to research, write, edit, publish) to graphic design to HTML. This means I have less people to rely on while saving a fortune in costs as well as having more editorial control. Don’t get me wrong, I – and Paul – would love to have a bigger team supporting us but the reality is we don’t have the money at the moment, and don’t have the time to put in for a funding bid. Upskilling is not only a means of ensuring this project maintains momentum but it also provides the kind of stimulation and variety that a creative needs to get up early in the morning and head to bed late.

The 12 fragments will be published on the memory theatre in September to coincide with Lawrence and Millett’s birthdays.