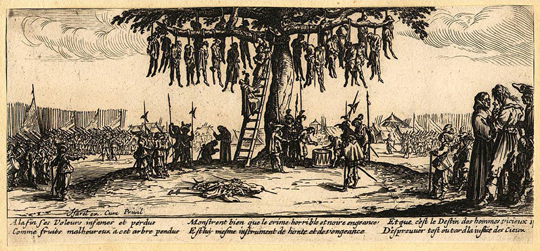

Jacques Callot, The miseries of war; No. 11, “The Hanging”, 1632

The following review was first published in The Spokesman Issue 133: Socially Useful Production

Hillary Chute puts forward a convincing and comprehensive argument that comics as a medium are perfectly positioned to act as documentary, as a form of witnessing, as a means of engaging and prodding history (particularly war-generated and traumatic histories). The artist is able to enter spaces that have previously gone unreported either due to censorship – there are no photographs from the torture chamber – or because many stories of ordinary lives have simply been ignored because they do not fit snugly into dominant ideologies.

Culture doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is the product of a never ending struggle to make sense of the world and our lives. If there is one thing that links all people, no matter what our religion, gender, sexuality or postcode, it is war. We’ve been kicking the living shit out of each other for centuries for a whole variety of reasons. Therefore a central question throughout the book is how war generates new forms of visual-verbal witness. And this is what makes this account so important. It is the first sustained critical study of documentary comics.

To do this, Chute blends a mixture of cultural studies, semiotics (textual analysis), literary theory, case studies, history, and critical theory from the likes of Bernard Latour, Roland Barthes and Judith Butler, to ensure a compact genealogy of her subject matter. Although it is largely accessible in tone, you will have to dip into the dictionary on occasion as it can get a little academic at times, although nothing to put off a confident reader. And if you do get lost there are eighty pages of footnotes offering support.

Chute identifies key artists who specialise in visualising war and death from across the ages in Callot, Goya (see above), Nakazawa, Spiegelman and Sacco. To contextualise her arguments we are provided with key illustrations from each artist, all of which are analysed in precise detail to enable a better understanding of their approach. For example, we are taken back to the Thirty Years War via Jacques Callot’s aptly named The Miseries of War which captures the complete disregard for the suffering of others. “The force of its mode of witness is in its attention to observing and revealing endemic suffering on all sides of war” writes Chute, where even ruthless soldiers are “subjected to atrocious acts of punishment for committing atrocity.” The dog is not so much chasing its tail but ripping it to shreds. These intimate portraits position Callot as the “first great reporter-artist”. Chute then shows how Callot’s work would influence court artist Goya, whose eighty three etchings of atrocities in Disasters of War begin with haunting first-person modes of address. “This I Saw” or “This is how it happened” send shivers down your spine through their complete casualness.

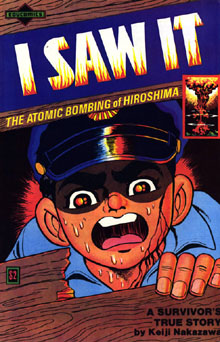

Disaster Drawn positions contemporary comics as part of a long trajectory of works that have each informed and created new idioms, practices and typologies of expression. To fully understand their significance “the context of the text must be part of the reading of the text”. Let’s take 1972, which Chute defines as a crucial moment as this is when both sides of the globe came together to bear witness to the very worst atrocities of waring nations. In the East, Hiroshima survivor Keiji Nakazawa’s eyewitness account Ore Wa Mita (I Saw It) would spawn “atomic bomb manga” and break down cultural taboos that had previously induced silence surrounding the subject. While in the West, Art Spiegelman’s Maus would depict Nazism through a very personal secondary account of Spiegelman’s own family’s survival of the Poland death camps.

The reason that this new genre emerged at this historical moment is the previous decades had paved the way forward for greater openness and expression, thanks to the battles fought around identity politics (race, sexuality, gender) as well as growing anti-war protests across the world brought about by the latest war in Vietnam. These issues couldn’t be spun or swept under the carpet anymore, thanks to the mass ownership of television which brought all of this death to glorious life in colour on the screen. Critic Michael Arlen (1966) described this mediation as ushering in the “living-room war” and Chute argues that this led to other countries, particularly Japan, to reflect on the past. It is worth noting, however, as Jean Baudrillard has in his collection of three essays The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, that we’re become increasingly desensitized to violence and now instead we witness stylized, selective misrepresentations of conflict through simulacra. Television may have paved the way forward for documenting certain conversations around war but it now functions as a passive medium.

Source: Wikipedia

Comics on the other hand, particularly personalised accounts, bring a more human face to suffering and can push the conversation in new directions. Keiji Nakazawa was six when Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. He was saved purely because a wall fell on him and protected him from the heat of the blast. His friend’s mother, who he had been stood next to, was instantly transformed into a blackened corpse. It was “violence so extreme it appears abstract.” I’ve read a lot about survivor guilt, particularly in the work of Primo Levi. But until reading this book I had never heard of survivors of an atomic bomb suffering stigmatisation due to cultural anxieties and misinformation. In Japan this is known as hibakushu (explosion-affected people) whereby survivors are treated like lepers.

Nakazawa’s mother was pregnant at the time and out of the city when the bomb was dropped. When she returned home the shock was so much she gave birth there and then on the street. The child didn’t last long. His mother died in 1966 and was cremated. It is a Japanese funeral practice, after a body has been cremated, for relatives to select major bones and place them in an urn. Due to the radiation, her bones had disintegrated. There was no tangible evidence left of her. Consequently, Nakazawa has made the atomic bomb the focus of his creative endeavours. His mother has become tangible by documenting her story. He has helped break down cultural taboos by daring to talk about them. He will not be shamed. Phew.

Usually I judge a book by how long it takes me to read it and this book took a staggering five months. Usually this would be a bad sign but there’s a more pragmatic reason for my slowness at turning the page. I was so drawn in by stories such as Keiji Nakazawam, that I had to pause and go and read his, and the other featured artists, comics. So through one review book I ended up reading twenty. Talking of which, readers may want to try Hydrogen Bomb Funnies (1970) by Robert Crumb in which his character Mr. Sketchum writes a letter to Bertrand Russell, believing he may like what he has to say. He steps out on a glorious hot day and happily marches down to the post box full of hope. I won’t tell you the ending. Let’s just end on hope.

Usually I judge a book by how long it takes me to read it and this book took a staggering five months. Usually this would be a bad sign but there’s a more pragmatic reason for my slowness at turning the page. I was so drawn in by stories such as Keiji Nakazawam, that I had to pause and go and read his, and the other featured artists, comics. So through one review book I ended up reading twenty. Talking of which, readers may want to try Hydrogen Bomb Funnies (1970) by Robert Crumb in which his character Mr. Sketchum writes a letter to Bertrand Russell, believing he may like what he has to say. He steps out on a glorious hot day and happily marches down to the post box full of hope. I won’t tell you the ending. Let’s just end on hope.

RELATED READING

- Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form, Hillary L Chute, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016. £25.95 HB

- The Spokesman: Issue 133. Tony Simpson (ed). Spokesman Books. £6

- Disaster Drawn and the Art of Joe Sacco. Dawn of the Unread blog.