For the past year I’ve been an occasional mentor to Charlie Davis, an Assistant Professor in Higher Education at the University of Nottingham, who has been investigating issues faced by academics of working class heritage. The results were then illustrated in three interactive comics, each with a distinct theme:

– Comic 1: Roots and routes into academia (What it means to be an academic of working-class heritage)

– Comic 2: Navigating the unknown: career journeys into and through academia (Career routes into and through academia)

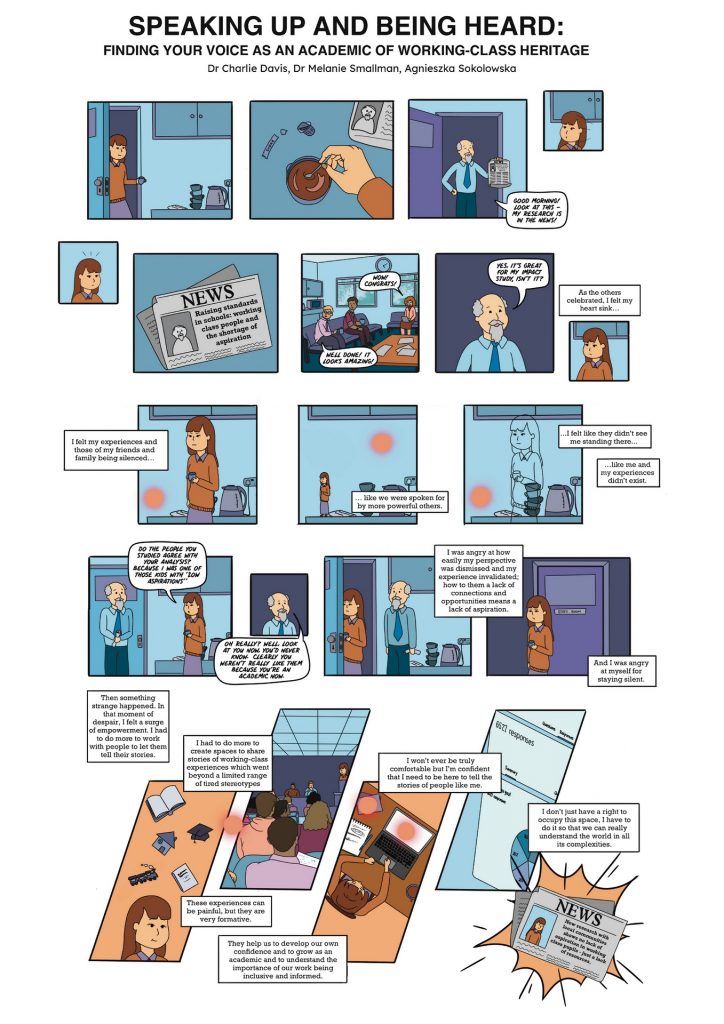

– Comic 3: Speaking up and being heard: finding your voice as an academic of working-class heritage (Developing epistemic confidence)

Class is a difficult thing to define and is influenced by various factors such as: confidence, wealth, culture, geography, occupation, attitude, and much more. Consequently, many working class people do not enter post graduate studies because of financial restrictions. I was only able to do my M.A because I was awarded a full AHRB scholarship – at the time I was a single parent and primary carer for my mother. The M.A transformed my life and opened the door to my current (part-time) career in academia where I’m paid to write and develop modules around my research interests in digital storytelling and literary heritage. I still struggle to convince myself that what I’m doing is work.

I was the first person in my family to go to university. My friends laughed. My brother wanted to know what we did – he’s a builder who deals (and bills) in tangibles. Skimming a wall with plaster is a productive use of time whereas reading a book is an indulgence. Consequently, studying was seen as a fad, and, most likely, a strategy to get out of doing a proper job. You battle with these attitudes when studying. Instead of questioning the theory you are reading you question whether you should be reading in the beginning.

Universities are rife with snobbery. I experience this internally: ‘Oh, you teach Creative Writing,’ and then for being an academic on a ‘Teaching and Practice pathway’ rather than the nobler pursuit of research. My practice is writing. There is nothing I want to do in the world other than write, so this category suits me fine, thank you very much. Prejudice exists externally, too: ‘Oh, you’re at Nottingham Trent. I see. One of the Polys.’ When you add class into the equation it’s no wonder that so many working class academics feel like imposters or unwelcome, particularly in Russell Group universities, the focus of Charlie’s research.

I’ve been working on a series of comics challenging stereotypes called Whatever People Say I Am, so I was very interested in Charlie’s desire to address perceptions and myths associated with working class academics. Charlie did this by forming story circles where participants shared their experiences. Then they drilled deeper into this data and co-produced comics based on composite stories.

I love this way of working because it ensures that everyone has a say in how they are represented at each stage of the process. The embedding of additional research material in the comic – such as audio recording – provides another layer of meaning and an opportunity for the reader to dig deeper into the topic. This is a technique that we pioneered in Dawn of the Unread.

Considering this is Charlie’s first foray into comics, he’s done a fab job. It’s the perfect medium to begin difficult discussions around identity. You can read more about his project by visiting his website here.

Further Reading Regarding Charlie’s Work.

- Charlie Davis Staff Profile

-

Davis, C, Rivlin, P, Mottershaw, S, Mihut, G, Matthews, A and Matthews, B, 2022. Creating SoTL communities through critical storytelling: reflections on a participatory study with Russell Group academics of working-class heritage In: EUROSoTL 2022.

-

2022. Coming Home Frances St Press. Available at: https://sofizine.com/latest-edition/edition-12/

-

Davis, C, 2021. Challenging the teaching excellence framework: diversity deficits in higher education evaluations Educational Review.

-

Davis, C, 2021. Creating a research-engaged pedagogy to support vocational learners transitioning into higher education Youth Circulations.