Photo by Paul Fillingham.

The following article was originally published in the August issue of the Southwell Folio. This is a magazine edited together by Penny Young which will sadly cease publication at the end of December.

In 2014 I created an online graphic novel serial called Dawn of the Unread. The narrative conceit is that, incensed by the closures of libraries and low literacy in 21st-century Britain, Nottingham’s most famous dead authors return from the grave to wreak revenge. It’s at this point I should make a confession: I am not an expert in graphic novels. In fact, prior to the project I didn’t even read graphic novels. But it was the right medium for my target audience: reluctant readers.

As far as I’m concerned, illiteracy is a form of child abuse. And Britain’s never had it so good when it comes to this shameful social problem. According to a major study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), England holds the unenviable title of 22nd most illiterate country out of 24 industrialised nations. The study involved over 166,000 adults and went as far as to suggest the potential threat of “downward mobility”, whereby the younger population is less well educated than the older generation. Not what you’d expect in the ‘Information Age’.

Literacy is a particular problem in Nottingham. Recent figures suggest six out of ten teenagers leave school without five A* to C GCSE grades, including English and maths. We were recently ranked worst in the East Midlands for level two SATs results with 77 per cent gaining a level four or higher, below the 79 per cent national average. It’s a right mess and it makes me furious which is why I decided to do something about it. But we’re getting somewhere. Dawn of the Unread was vital in Nottingham being accredited as a UNESCO City of Literature and was used as an example of best practice in how to engage youth through digital technology. The City of Literature has now become an educational charity, with improving literacy their number one goal. I’m proud to have helped contribute to this conversation.

There’s been much written about the diminishing attention spans of our ‘youtube generation’ so thrusting ‘complex’ books on them isn’t going to help. If teenagers reading levels are already low, Shakespeare will only frustrate them further. Instead, I’ve tried to create a thirst for knowledge. To tease, tantalise and inspire by creating a series of 8 page comics which offer snippets into the lives of our incredible diverse and rebellious literary heritage. By using a wide variety of styles (reportage, poetry, fiction, gallows ballad) and combining different writers and artists, I hope that one of the stories may appeal. And if teenagers go on to the library to get out books, it will be because they want to learn more.

Photo by City of Literature.

So what is a graphic novel?

The term ‘graphic novel’ was first coined by Richard Kyle in an article for Capa-Alpha in 1964. But to be blunt, it’s just a means of making a comic sound more respectable. There is a prevailing attitude that comics are a form of dumbing down reading and that they are somehow inferior to literature with a big (or little) L. But having edited together 16 issues of Dawn of the Unread I can assure you that comics are anything but simple.

A comic is a kind of creative production line which involves: a writer, artist, colourist and letterer. The writer and artist are co-authors of the text and it’s vital that both get to express themselves equally. Therefore a writer must not be over descriptive as a broad range of ideas can be illustrated by the artist. The style of the artist can also reflect the theme of the story. I selected Carol Swain to illustrate the life of Alan Sillitoe (issue 12) because she draws in rough crayon on textured paper. What better way to subtly reflect the gritty realism of Sillitoe’s writing?

Each page of a comic consists of a limited series of panels (frames) which function to create a sequential pace to the story. This helps you feel the action unfolding and is similar in purpose to a storyboard. How characters react in frames offers a further layer of meaning too. The Gotham Fool (issue 4) is the tale of a group of people who feigned madness in order to avoid building a highway for King John. At the time madness was perceived to be contagious. Labels are a means of reducing identity to one fixed point, so we reflected this in the art by the way characters are not constrained by panels. They break out into the gutter (the space between panels), suggesting a degree of freedom.

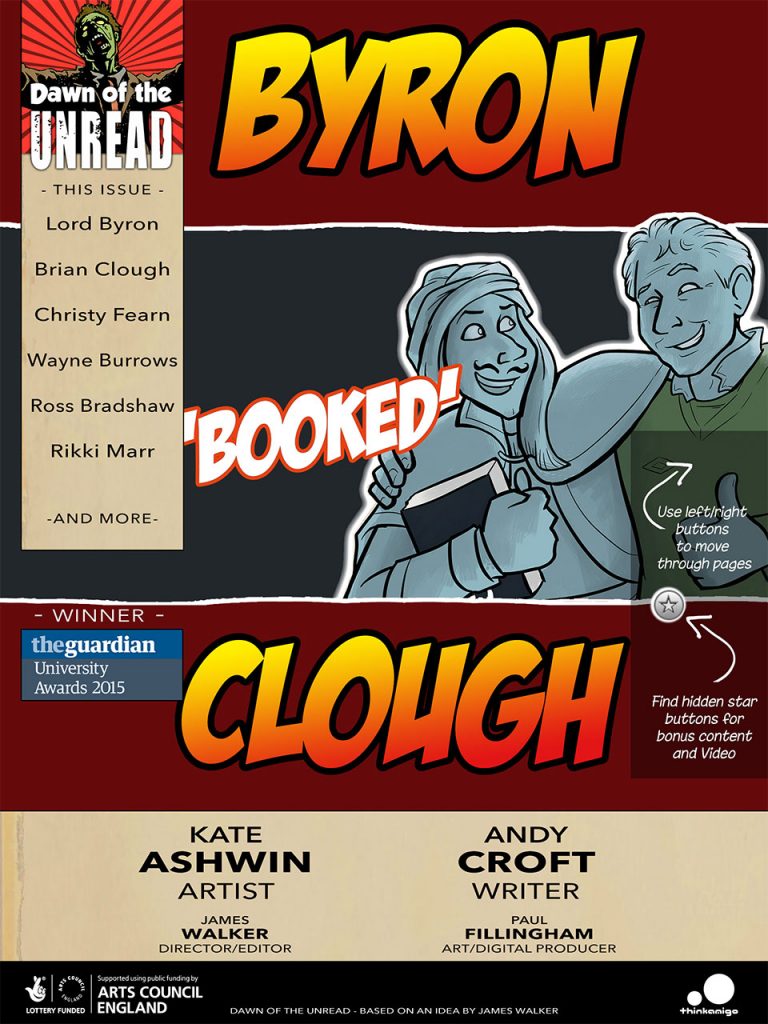

Artwork by Dawn of the Unread.

Colour is also an important signifier of meaning. When we created the charismatic hybrid Byron Clough (issue 5) we used bright colours and thick black lines, just to stop verisimilitude and reinforce that he was imaginary. Likewise the use of font (letterer) can capture the essence of a character. In issue 11 we explored Geoffrey Trease’s debut novel Bows Against the Barons which features Robin Hood. The font is sharp and crisp, as you would expect from a master archer.

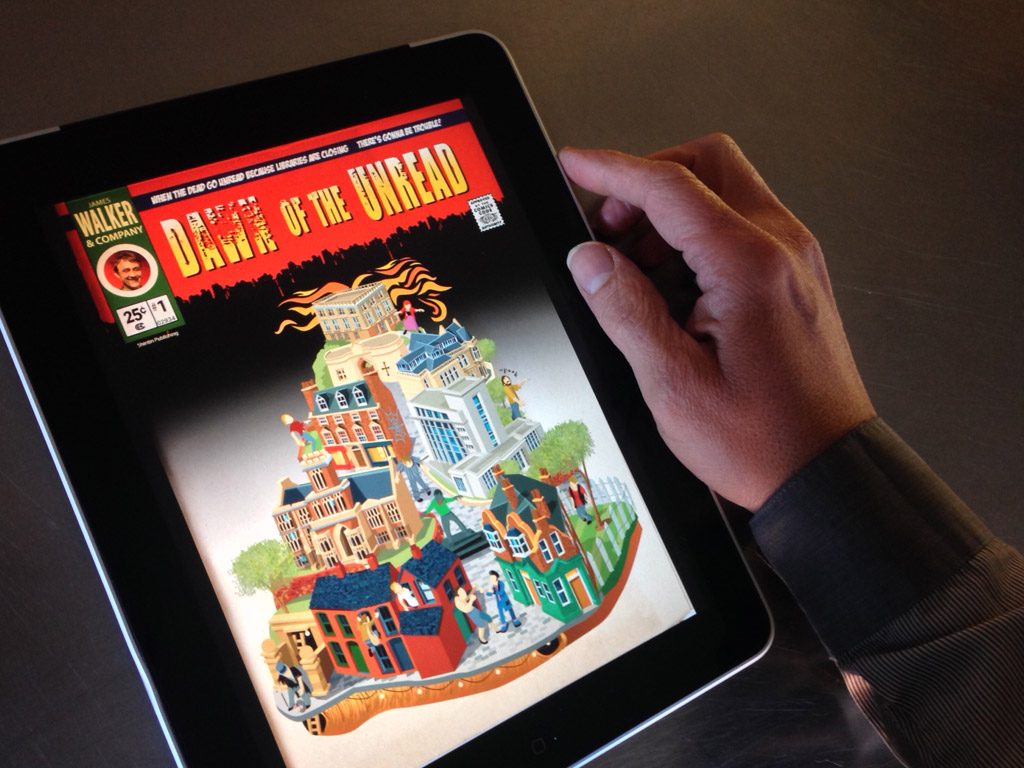

By making Dawn of the Unread available online I was able to utilise the potential of digital technology by including embedded content. This means that when you click on a star icon within a panel it provides contextual information, such as essays. This helped facilitate more insightful discussions for more confident readers who wanted to go deeper into the text. As far as I’m aware nobody has done this before.

Finally we created an App that enabled users to ‘play’ Dawn of the Unread. This consisted of a series of tasks, bringing in a gaming element to our project. By using a wide variety of styles and storylines, making the comic available across media platforms, and providing different narrative routes through the text, I hope that there is something for all types of readers.

There will be a book launch for Dawn of the Unread as part of Nottingham’s Festival of Literature on 11 November (7.30- 9pm) Antenna, Beck Street, Nottingham. Tickets are £5 but you get £3 off a book.