Bletchley Park county estate was the secret codebreaking headquarters during WWII where Alan Turing and co would crack the Enigma code and help bring an end to the war by an estimated two years, saving many lives in the process.

To ensure absolute secrecy, no transmission ariels were allowed to protrude from the buildings as this might raise suspicions with passing bombers. Instead, hundreds of bike riders were tasked with getting important information and updates to those who mattered. The rural location meant it was less likely to be targeted, but Bletchley was chosen for more pragmatic reasons. It was smack bang in the middle of the main train route between Cambridge and Oxford, meaning the best mathematicians could be brought up quickly and at short notice. Workers were allocated to specific huts and teams were forbidden from talking about what they were doing both during and after the war or else face charges of treason and imprisonment. So while returning soldiers were glorified, the codebreakers could only say they had menial office jobs. Such integrity seems unimaginable today where we are encouraged to share every experience, as this article demonstrates.

75% of the work force were women and Alan Turing, a gay man, was prosecuted for homosexual acts in 1952. As punishment, he accepted a hormone treatment known as ‘chemical castration’ rather than go to prison. In 1954, aged 41, he committed suicide from cyanide poisoning. He was granted a pardon in 2013 by then PM Gordon Brown after a national campaign. In 2017, the ‘Alan Turing Law’ was introduced which retroactively pardoned men cautioned or convicted under historical legislation that outlawed homosexual acts. This feels particularly relevant today given the attack by the Trump administration on diversity and LGBTQ+ identities. To put this into context, Slate reports Trump ‘fired the Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to replace him with a white retired general, who is both significantly less qualified for the job by military standards and ineligible for the role by those same military standards’. So much for fairness and meritocracy. Bletchley was largely shaped by a gay man and a 75% female workforce, demonstrating the value of a diverse workplace.

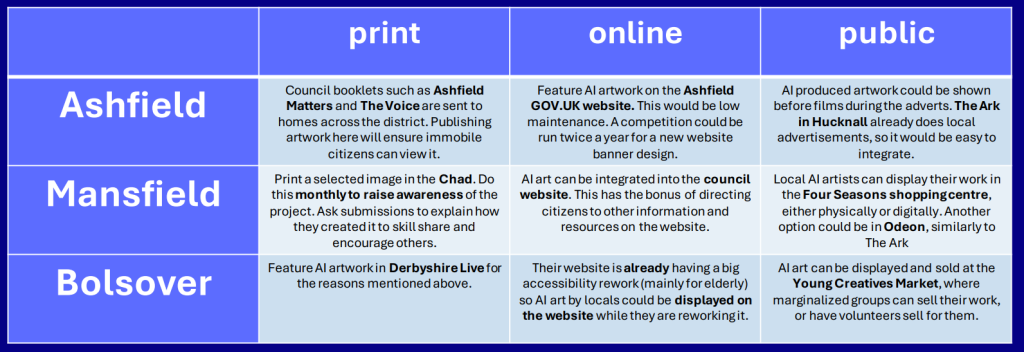

Due to its historic links to computing, Bletchley was the location for the first AI Safety Summit in 2013. It currently has an exhibition on ‘The Age of AI’ which is why I visited with students from Nottingham Trent University. We are about to embark on a research trip to Europe to see how AI and creative technology can help better engage younger people in the political process and civic engagement. Our research is fed back to councillors from Ashfield, Bolsover, and Mansfield to help inform policy and investment and builds on a research trip last year where we visited the first AI Gallery in Europe.

I feel ambivalent about AI. As a writer, I understand that stories are incredibly personal and the result of our unique social situations. We write stories because we want to share our experiences of life with the world. AI does not have experience or empathy or history and so I am dismissive of any fiction it produces because it is not shaped by personal experience and so lacks the most fundamental quality of persuasion, ethos – the credibility of the speaker – to borrow from Aristotle.

But I do find myself increasingly turning to programmes like Chat GPT as a personal research assistant when I need to find the answer to an immediate question that will help me with setting a scene, such as what wild flowers grow in the hedgerow at a specific times of the year. And as someone who produces a monthly video essay based on the letters of D.H. Lawrence, I sometimes have difficulties sourcing an image to match the script, such as for the video above. I used a programme like DeepAI to generate an image of a ‘squashed friend locus beetle’ which Lawrence was aghast at when he encountered it in a market in Mexico in November 1924. Quite rightly, you have to flag the video up as including ‘artificial or synthetic content’ on YouTube.

One area of interest at the Bletchley exhibition regarded AI Influencers. These, like their human equivalents, are mainly used for branding and selling products. But what if we were able to create an AI Influencer related to our research aim? A virtual assistant who could break down complex ideas to make the political process more accessible, or was able to flag up flaws in populist conspiracy theories, explicitly explaining how Tommy Robinson or Andrew Tate were not victims of the Deep State but people who have broken specific laws.

Part of the drive towards conspiracy theories is firmly grounded in reality. Lots of people, particularly white men, feel alienated and ignored, and so it is understandable – to an extent – why they may find belonging in spaces where they feel listened to. Any kind of AI support would need to address these nuances but perhaps introduce more positive or alternative means of belonging than those determined by social media algorithms.

If you have any suggestions about our research question, please do get in contact. And whether you like AI or not, visit Bletchley at some point in your life to pay respect to the many unknown people who dedicated their lives – without recognition – to help bring an end to the war.

Bletchley Park, Sherwood Dr, Bletchley, Milton Keynes MK3 6EB. The AI exhibition is on till 2026. Visit the website here.