‘Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.’ – Edgar Degas

Earlier this year, I headed off on a research trip across Europe with a group of students to explore the potential of AI and social inclusion. This is an annual research trip funded by NTU Global. Our findings were fed back to councillors from Ashfield, Bolsover, and Mansfield with the hope that it may inform future policy. Suggestions had to be affordable, realistic, and sustainable, and take into consideration the ‘invisible labour’ required to maintain them in the future.

We took our main inspiration from Dead End Gallery in Amsterdam, the first AI Gallery in Europe. The gallery was established because nobody would host their AI artwork due to copyright issues. Presumably this was based on two concerns: Only humans can be granted copyright so who owns the artwork? Given the controversy created by David Slater’s ‘Monkey Selfie,’ this is understandable. In terms of generating images, what are they based on and how is the information sourced? Perhaps they wanted to avoid scenarios such as the Alden Capital lawsuit where eight U.S. newspapers are suing OpenAI and Microsoft for copyright infringement.

Our main concern related to creativity. We create art because we want to share our stories with the world and these stories are based on our unique social circumstances and experiences. How could AI create art when it has no history or lived experience?

Dead End Gallery have attempted to address this question of authenticity by creating profiles for its artists Irisa Nova, Maximilian Hoekstra, Lily Chen, and Amani Jones. Each artist is fed a series of questions (Do you have a partner? What is your favourite colour?) to slowly develop a profile and personality.

To ensure integrity, they created an AI curator which decides whether art submitted by the AI artists is displayed in the gallery. To be included, artists must score 8 or above out of 10. Likewise, they have attempted to replicate the process of learning an artist goes through by feeding the AI ‘drugs’ to see if this would lead to more surreal artworks or a different artistic outlook. This was partly to address criticisms that AI artwork lacks emotion.

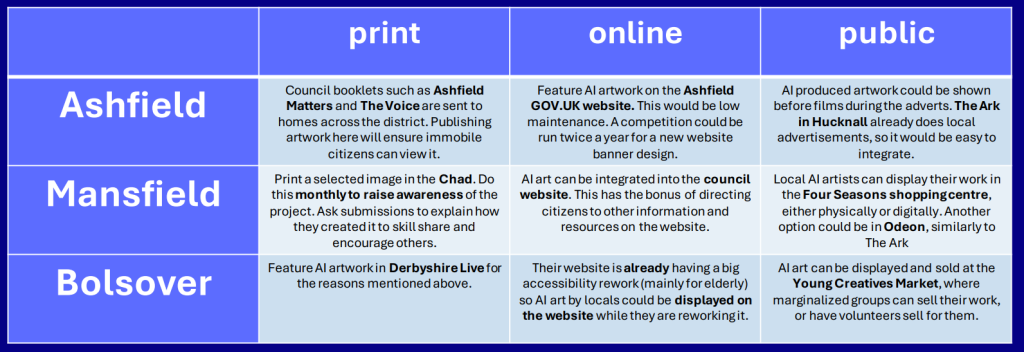

Edgar Degas once argued that ‘Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.’ We want to develop this principle further and ask, how can AI help us see marginalised people? With training and support, AI has the potential to help marginalised groups participate in culture by creating art from home. This could be published at low cost across a variety of media to ensure to reaches a broad audience, as indicated in the table below.

But it’s always good to think big, too.

Ashfield has recently invested in the Automated Distribution and Manufacturing Centre (ADMC) which is a national centre of excellence for automation. Investing in the first AI Gallery in Britain would help develop the area further as a hub of digital innovation. It could act as a teaching space (perfect for school trips) or lead to new courses being developed at local education establishments. This would form part of a ‘clustering’ strategy to help regenerate the area.

It is worth noting that younger people, such as my students, feel excluded from politics, and that their concerns about the economy and the climate go unheard. Participating in this research project and having access to decision makers has helped them see they can make a difference and that their opinions are valued. Indeed, one council member has invited all the research groups to feed back their ideas at an Executive Board meeting. It is a fantastic opportunity, and has certainly restored my faith in the political process, at least on a local level.

Dead End Gallery, Oude Braak 16A, 1012 PS Amsterdam

Tel. +31 (0)6-33677773 ai@deadendgallery.nl