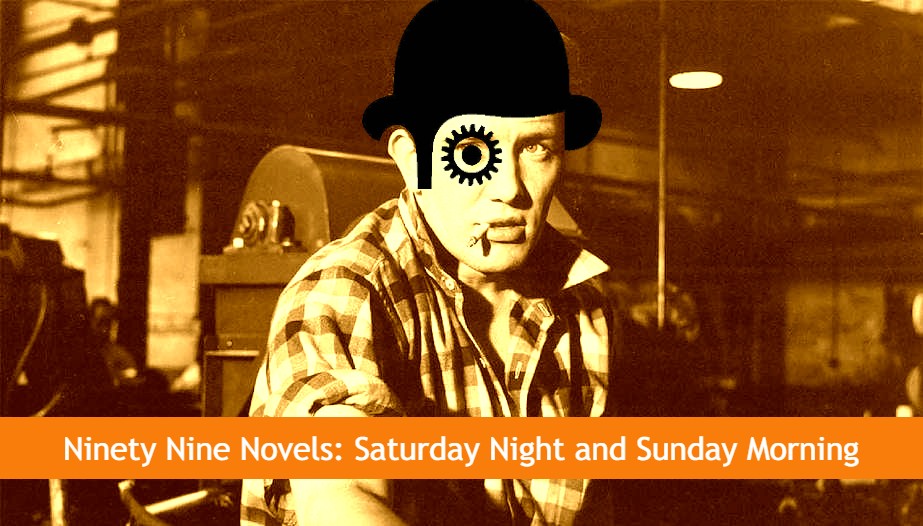

Photo from Karel Reisk collection at BFI.

Anthony Burgess (25 February 1917 – 22 November 1993) was a prolific writer who produced poetry, plays and broadcasts while also building his reputation as a literary critic and linguist. He came pretty late to fiction, turning 39 when Time for a Tiger was published in 1956. Thirty or so novels later, he is best known for his dystopian satire, A Clockwork Orange, which would gain cult status when Stanley Kubrick adapted it for the screen in 1971. This seems a bit reductive, particularly given that he composed over 250 musical works over 60 years. These varied in genre and style and included symphonies, concertos and opera.

Burgess came from a musical family. His mother was a Music Hall singer and dancer and his father played piano. He once wrote: ‘I wish people would think of me as a musician who writes novels, instead of a novelist who writes music on the side’. In this blog I am going to do neither and instead turn to a very specific piece of his non-fiction published in 1984.

Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939 — A Personal Choice is a pretty self-explanatory title and covers a 44-year span between 1939 and 1983, starting with James Joyce and finishing with Norman Mailer. Some authors get two mentions whereas Aldous Huxley pulls off a hat trick with After Many a Summer (1939), Ape and Essence (1948), and Island (1962).

Burgess was a vociferous reader who famously reviewed 350 novels in just over two years at the Yorkshire Post. Presumably he didn’t sleep or eat during that time. His background in journalism and broad knowledge of literature led him to pen Ninety-Nine novels in two weeks. Like all reading lists, it’s intended to provoke discussion and debate – hence the absence of the hundredth novel. ‘If you disagree violently with some of my choices I shall be pleased. We arrive at values only through dialectic’ he writes.

The International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester are currently running a podcast series, with each episode dedicated to a book on the list. I was invited to talk about Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958). The book was the first Pan paperback to sell a million copies, and like A Clockwork Orange, would forever become synonymous with the author.

In his introduction to Ninety-Nine Novels, Burgess says, ‘I believe that the primary substance I have considered in making my selection is human character. It is the Godlike task of the novelist to create human beings whom we accept as living creatures filled with complexities and armed with free will’. This is certainly true of Arthur Seaton, the charismatic anti-hero of Sillitoe’s debut novel who craves pleasure at every opportunity, no matter who he hurts along the way: “I’m me and nobody else, and whatever people think I am or say I am, that’s what I’m not, because they don’t know a bloody thing about me.”

‘As novels are about the ways in which human beings behave,’ writes Burgess ‘they tend to imply a judgement of behaviour’. What makes Saturday Night and Sunday Morning so authentic is the complete lack of authorial judgement. Sillitoe describes everything as it is. There’s no pandering to sensibilities or fear of moral outrage. This is why publishers originally turned the book down – because they felt the working classes needed a more edifying narrative than the violent environment Sillitoe portrayed. To put this into context, John Braine’s Room at the Top is on Burgess’s list, which Peter Green described as like a ‘vicar’s tea party’ in comparison.

Burgess isn’t completely effusive, describing Sillitoe’s writing as ‘verbose and sprawling, undisciplined’. Although I partly agree with this, I don’t see it as a fault. Sillitoe was a self-taught writer. He didn’t go to university or enrol on a creative writing course. He figured things out for himself. It’s this that gives his writing the rough edges and authenticity.

Some writers are so obsessed with form that you become aware that you’re reading a very well written book. With Sillitoe it’s different. You’re not reading a book. You’re stood at the lathe. You can smell the factory. You can hear people gossiping about you. It’s a different kind of verisimilitude that’s only possible when you write with your ear.

The podcast is hosted by Graham Foster who is the former editor of Transmission. He was one of the first people to publish one of my short stories (The Loneliness of the Dartford Toll Operator) – about a woman who touches 1000’s of hands a day as money is exchanged yet never gets to know anyone on a meaningful level. You can tell it’s an old story (from the mid Noughties) because now there are no toll operators. You have to pay in advance and register your number plate. I found out the hard way last year when I was fined. But that’s another story.

You can listen to the Ninety-Nine Novels podcast on Soundcloud

International Anthony Burgess Foundation, Engine House, Chorlton Mill, 3 Cambridge Street, Manchester. M1 5BY

This blog was originally published on the Nottingham City of Literature website on 27 June 2022.