One thing I am quickly learning about editing together Sillitoe: Then and Now for The Space is how much retrospective creativity is involved. By this I mean finding a narrative thread that draws together all of your writers in a manner that seems deliberate and well thought out. Our project explores five locations from the novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. These are; Old Market Square, The White Horse, Raleigh, Trent and the Goose Fair. The order for these has changed at least three times since I originally put together the plan with Paul Fillingham. Only the Goose Fair has always remained the last event as this falls in October when the Mobile App is launched.

Market Square appeared first for the simple reason that we had content. The White Horse came next because I had immediate contact with Al Needham and so could talk through ideas face-to-face rather than via email. Derrick Buttress was originally asked to write about each decade he had experienced in the Market Square. I was expecting something leading up to the present but when I read his first couple of pieces from the 1930s and 40s I realised it was better if he gave context to the novel by writing only about the decades leading up to 1958. Al Needham has now picked up this journey and takes us on from 1958 to the present through a talk about his life through pubs. This wasn’t planned. It just happened that his parents were drinking during the 50s and so the natural link was made. It’s my job to ensure writers mirror each other and that there is a spine holding the content together. I never realised that so much of this would happen after, rather than before.

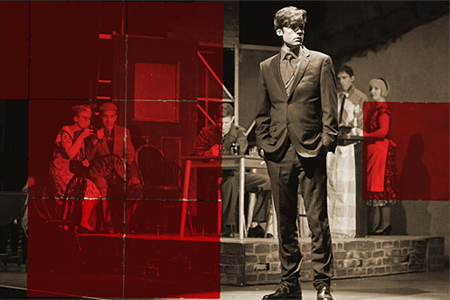

Another example of retrospective reasoning is through Seaton Rifles. This is where we (Neil Fulwood and I) imagine how Arthur Seaton would react to the observations of the five commissioned writers. So that the project isn’t text heavy I opted for these to be read out and asked a rising young star from Nottingham called Tom Keeling as he had recently played Arthur Seaton in the musical adaptation. This had numerous benefits. Firstly, the Alan Sillitoe Committee gets a cut from every production of the play which goes towards our statue fund. Therefore it’s in our interest if the musical tours nationally which becomes a possibility if we keep the lead actor in the media. His presence also means that we gain extra publicity by reaching actors/musicians/theatres. Building such partnerships is essential as we live and die by our statistics and so any opportunity to broaden our reach is welcome.

Tom’s reading was a lot softer than I imagined Arthur Seaton to be. This is probably because the Lancastrian tones of Albert Finney have become synonymous with the role. I was worried that it did not have the raw edge that people would expect and that this would open us up to criticism. The solution, then, was to approach Arthur Seaton not as a voice but as a spirit performed by different people, such as Todd Haynes did in his Bob Dylan movie I’m Not There. This then got me thinking about what a female Arthur Seaton would sound like as the book could quite conceivably have been written from a female perspective. Female factory workers of the period would have felt a greater sense of injustice than our iconic anti-hero given that a shift down at Raleigh was replaced by a shift at home sorting out the family. I suspect that the limited time they would’ve had to ‘have a good time’ would create far more outlandish behaviour than falling to the bottom of some stairs. And so what seems like a problem suddenly becomes part of the creative process. Writing is quite simply about finding patterns and my web grows more complex every day.

But I am not the only predator in the web. When the first Seaton Rifles was uploaded someone at the BBC changed the title to Arthur Seaton Rifles. This completely lost the subtle reference to the Jam song while becoming so explicit it felt insulting to the reader. I pointed this out to my mentor and thankfully it was changed. I wonder if anyone dares tinker with Will Self’s Kafka’s Wound for the London Review of Books? I suspect not.