In my previous life as a journalist, I developed the vital skill of reusing content. An interview with a writer could be used across multiple publications if you used your quotes judicially and changed the slant of each subsequent article. Likewise, a book review works as 100 words, 250 words, 1000 words, depending on the publication.

These principles of economy remain with me in education as I try to strike a balance between researching and writing content for new modules and taking on other commissions. It was with this in mind that I agreed to give my annual talk to the Leamington Literature Society on the emergence of the anti-hero in post-WWII literature as I was also researching the writing of Alan Sillitoe for a first-year module I lead called ‘Writing in a UNESCO City of Literature’.

I love giving talks to literary societies as the membership tends to be retired, educated, and with a bit of life under their belts. So conversations afterwards are animated and challenging and leave me thinking about things slightly differently than when I entered the building.

The anti-hero can be characterised as being morally ambiguous and at odds with society. Their appeal is they reflect the uncertainty, alienation, and cynicism of the post-war era, providing a more authentic and relatable way of understanding the human condition in a rapidly changing world.

The talk outlined eight key factors that had led to this outlook, one of which is disillusionment with traditional values. Having witnessed the horrors of war firsthand, many felt disillusioned by the ideals promoted during the war, such as patriotism, honour, and the concept of the “noble hero.” The horrors of war challenged previously held beliefs about good and evil and simplistic solutions to complex problems no longer appealed. Superman was out.

Arthur Seaton, the hard-working beer-guzzling anti-hero at the heart of Sillitoe’s debut novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, warns “yer never believe what the papers tell yer, do yer? If yer do then yer want yer brains testin’. They never tell owt but lies. That’s one thing I do know.” Goodness knows what he’d have made of Twitter.

Similarly, old values around class and etiquette are challenged when Arthur mocks a factory worker on his break “Some blokes ‘ud drink piss if it was handed to ‘em in china cups.” Seaton develops his own moral universe and is not swayed by perceived wisdom. He trusts nobody but himself and is ruthless in his pursuit of happiness. Charismatic and endlessly quotable, he’s a delight to read – though I’d steer clear of him if he was my neighbour.

If you want to learn the other seven factors, you’ll have to book my talk. But the fact that surprised the audience the most was Arthur Seaton earned more as a pieceworker in 1958 than a professional footballer. How times have changed…

I always leave my talks with a recommended reading list because the purpose of such talks is to get people reading, and hopefully with a different means of perceiving texts.

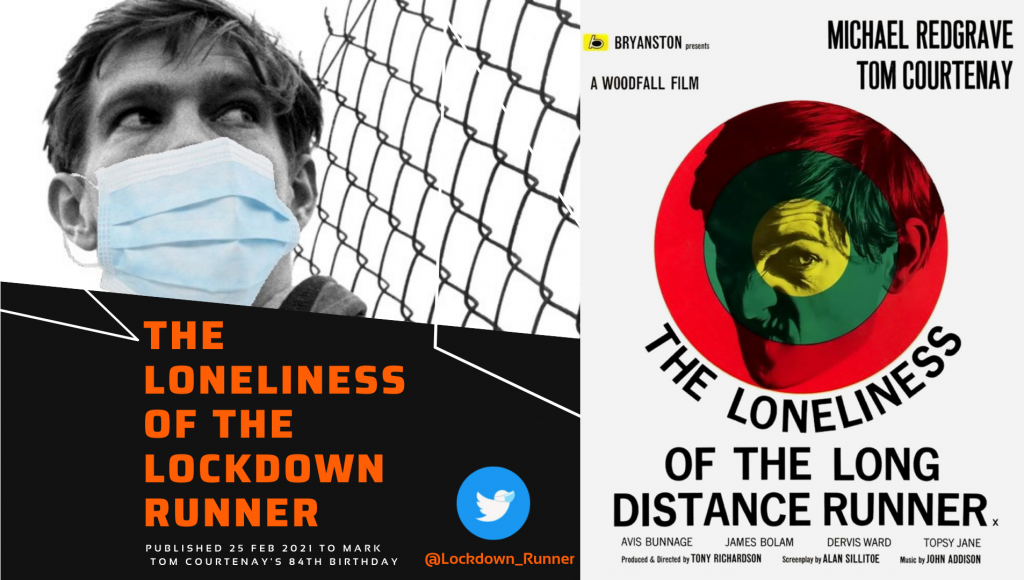

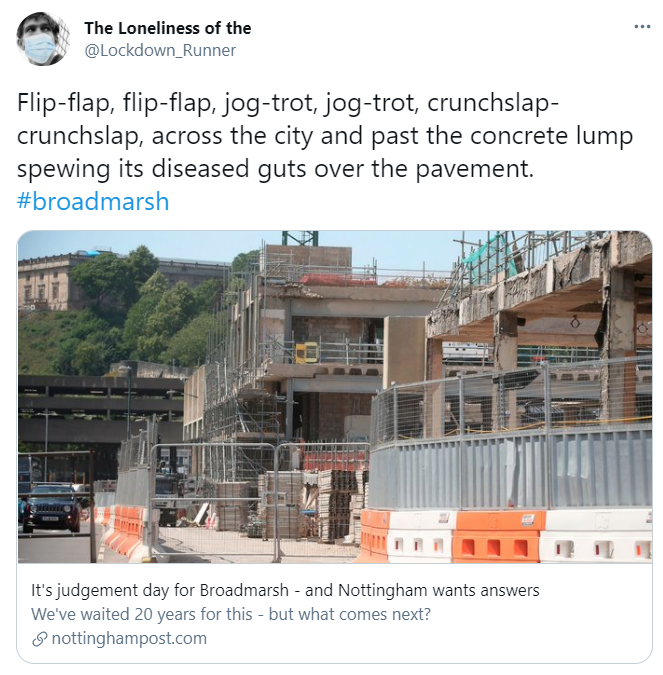

For anti-heroes in Sillitoe’s work, see Colin Smith in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1959), Arthur Seaton in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958), and Ernest Burton in A Man of his Time (2004).

For anti-heroes in post-WWII literature see Yossarian in Catch-22 (1961), Jim Dixon in Lucky Jim (1954), Joe Lampton in Room at the Top (1957), Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye (1951), and my favourite anti-hero of all time, Meursault in The Stranger (1942).

Links