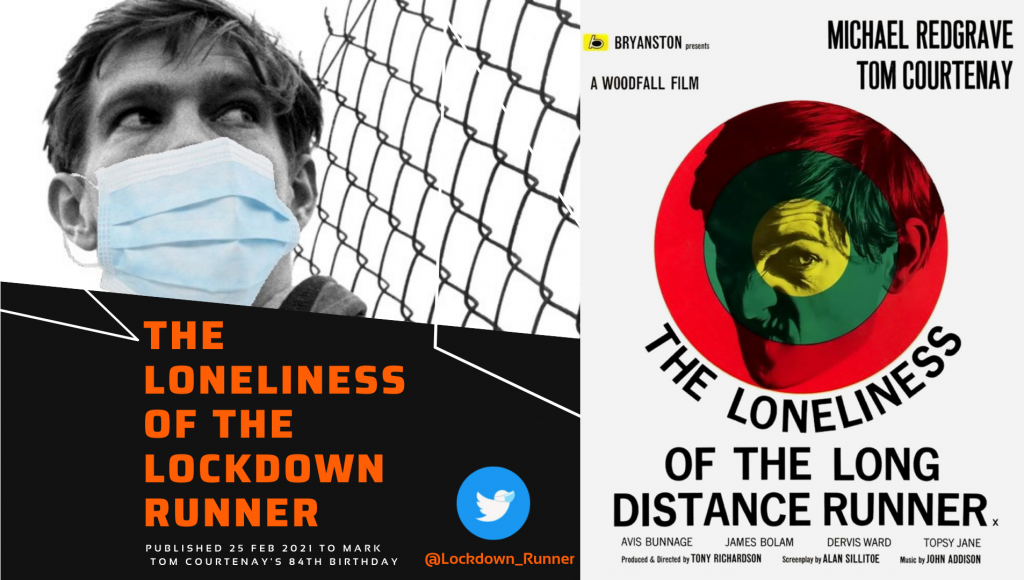

To mark the 84th birthday of Sir Tom Courtenay, who played Colin Smith in the film adaptation of Sillitoe’s 1959 short story The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, I’ve updated the tale for the lockdown generation. This second of two blogs explains why Twitter was the best medium for the project.

During my A-Levels, many moons ago, I binge read every book I could get my mucky paws on by Keith Waterhouse. Next up was Alan Sillitoe. When I’d read every kitchen sink novel and play of postwar Britain, I watched the British New Wave films. Sir Tom Courtenay played the part of two of these iconic figures: Colin Smith in Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Billy Fisher in Waterhouse’s Billy Liar. These books and films had a profound effect on me during those formative years, not least in terms of class, culture and identity.

To say thank you to Sir Tom, and as a means of passing time during lockdown, I decided to update Sillitoe’s story of defiance for the covid generation as The Loneliness of the Lockdown Runner. Sillitoe’s story is 17,209 words long. I broke it down to 100 tweets that were published over five days, starting on Thursday 25 Feb – to commemorate the 84th birthday of Sir Tom Courtenay, who played Colin Smith in the British New Wave film of 1962.

I chose Twitter for numerous reasons:

Twitter is a medium of constraint and constraint is a vital component of creativity. When you have a limited mode of expression you have to be economical with your choice of words as well as consider other ways in which you can utilize the medium to create meaning.

To create a ‘beat’ each set of 20 tweets had to end on a ‘page turner’ that would encourage people to come back and see what happened next. This also created another layer of constraint.

The form reflects the content – a story about someone running, taking slow thuds along the pavement, is, in some respects, like the methodical beat of a tweet.

Images and hyperlinks

Tweets can include images which enable another layer of meaning. This meant I could take stills from the film and update them to reflect themes from 2020. I was also able to mash-up covid slogans with popular cultural references.

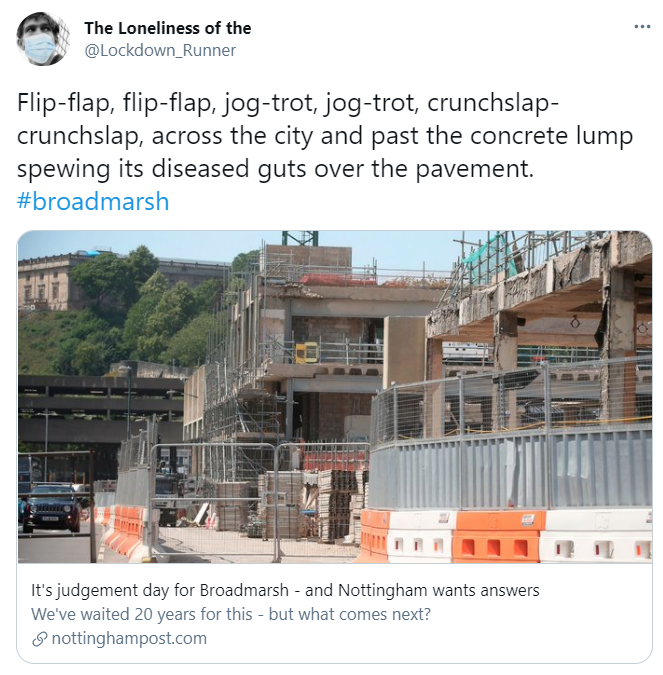

Sillitoe was born in Nottingham and set many of his novels and short stories here so I wanted to include images of the city in my updated version. For example, in Sillitoe’s story, Colin Smith is running in the countryside and mentions a giant oak. I changed this to the Royal Oak pub in Basford.

Tweets could include hyperlinks, enabling the story to document key events from March 2020 – masks being dropped on the floor, furlough, contradictions in policy, a divided nation – people who follow restrictions and rules, sloganism, Joe Wicks – all set against the backdrop of Trump, Farage and Brexit.

I love digital storytelling because of the intertexual references and layering of meaning it allows. This enables the story to broaden out and possibly draw in a wider audience who may not otherwise have read the original story. As much as I love digital storytelling, all of my projects are about reminding the ‘user’ they are primarily a ‘reader’ and so guiding them back to the original text.

Sillitoe did not go to university. He did not do a creative writing course. He refused to have his work edited. This is what gives his writing such a raw authentic voice – it does not have the polish of a good edit (and in some places would benefit from one). There has been much talk recently that there are no working-class writers anymore and this is hardly surprising given the process of getting your work read in the first instance. Agents act as the first form of gatekeeping and are (understandably) driven by how a voice fits into the market and what will shift copies rather than notions of authenticity and what makes a good read. And I very much doubt that a lot of working class writers – especially those who do not have a degree – have any idea of where to send a book to.

All of which is an added reason as to why I love digital storytelling so much – you have a platform that is accessible, you can say what you like without worrying about whether your words are marketable, and, should you have the inclination to do so, you have a quick and easy reference to refer publishers to should you wish to take your work down a traditional route.

Further Reading

- Twitter @Lockdown_Runner (twitter.com/Lockdown_Runner)

- Twitterature: Lockdown Runner Tweets (jameskwalker.co.uk)

- Twitterature: The Loneliness of the Lockdown Runner (jameskwalker.co.uk)

- Happy Birthday Sr Tom, here’s your prezzie (dawnoftheunread.wordpress.com)

- Reimagining Sillitoe during covid (leftlion.co.uk)

- Loneliness of the Lockdown Runner (nottinghamcityofliterature.com)

- Woodfall Films (woodfallfilm.co.uk)

- Publishers must act now to develop working-class writers, says report (guardian.com)