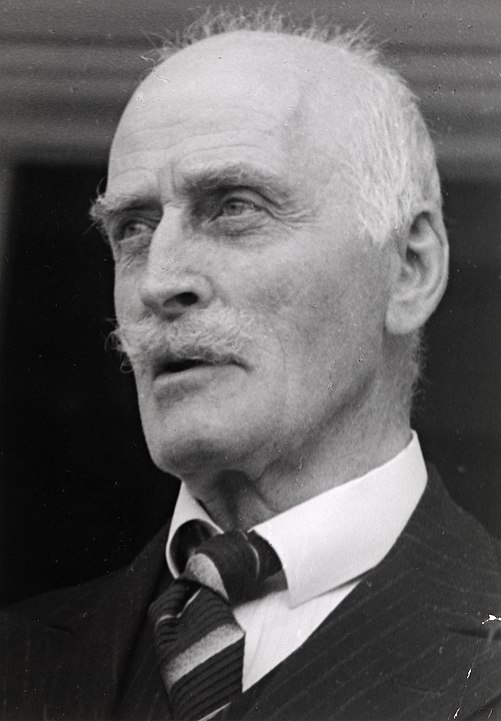

Knut Hamsun photo by Anders Beer Wilse. Eier: Nasjonalbiblioteket (bldsa_HA0341) Photo from wikipedia.

Hunger is one of my all time favourite books so I was delighted when Sarah chose it for book club. The recent edition comes with a fantastic forward by Paul Auster, which, as every reader knows, you read at the end so you can see gauge how clever you are. This edition also includes a breakdown of key differences between the three translations – a must for any word-obsessed bibliophile. I’ve not got to the stage yet where I need to read and compare all versions before learning Norwegian and reading it in its natural tongue, but it was very useful. A previous book club choice had been Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha (1922) and a poor translation clearly affected enjoyment for some. Translations offer a different context to our book group because our members span the globe; Russia, Germany, America, Italy and of course England. Consequently, poor translations can arouse as much debate as the actual narrative.

I’d suggested that the group forgo food in the spirit of the novel but our book group is really a foil for a meal and beer out – so this was never likely to happen. When the discussion started, Sarah was a little worried about what we might think of her as she’d just discovered that Knut Hamsun was an ardent Nazi sympathizer who’d sent his Noble prize medal for literature to Joseph Goebbels. Ah, the scourge of Wikipedia. I felt that we should continue this debate after we’d discussed the actual content of the book but there seemed to be general agreement that you can’t separate the person from the novel.

I’m cautious of retrospective analysis for two reasons. Firstly, Hamsun was also staunchly against British Imperialism and our involvement in the Boar War, deeming it far less egalitarian than I remember being taught at school. History is written by the winners and therefore it is only a matter of time before our own truths become challenged as new evidence emerges. (Was it necessary to drop an atomic bomb on Japan when the war was all but done? Did Britain really have to flatten Dresden? Can we really trust a country that goes to war and awards itself all of the contracts for rebuilding that country when it’s all done?) Secondly, unless you actually lived in that particular moment, I don’t think it’s possible to pass complete judgement on others. Psychological research proves conclusively that there is a massive disparity between attitudes and behaviour. Having said that, there is no way on this earth you can ever justify the mass genocide of people. To even rationalise it proves the point that we are always detached from history when looking through the rear view mirror. In this case, if Hamsun had any awareness at all of the genocide and torture camps then it is impossible to separate the person from the work. When I think of the book in this light I feel ashamed for still liking it so much and for continuing to recommend it to others. It’s just a brilliant book.

Clearly I have a literature bias because I have no difficulty whatsoever in refusing to ever read or watch anything by Frank Miller again after his ridiculous comments about the Occupy protesters. He called them ‘filthy’ – a common term used to reduce someone as subhuman (as with the Jewish rats in Nazi propaganda) and even worse, claiming some were ‘rapists’. What a twat. He went on to say ‘Wake up, pond scum. America is at war against a ruthless enemy.’