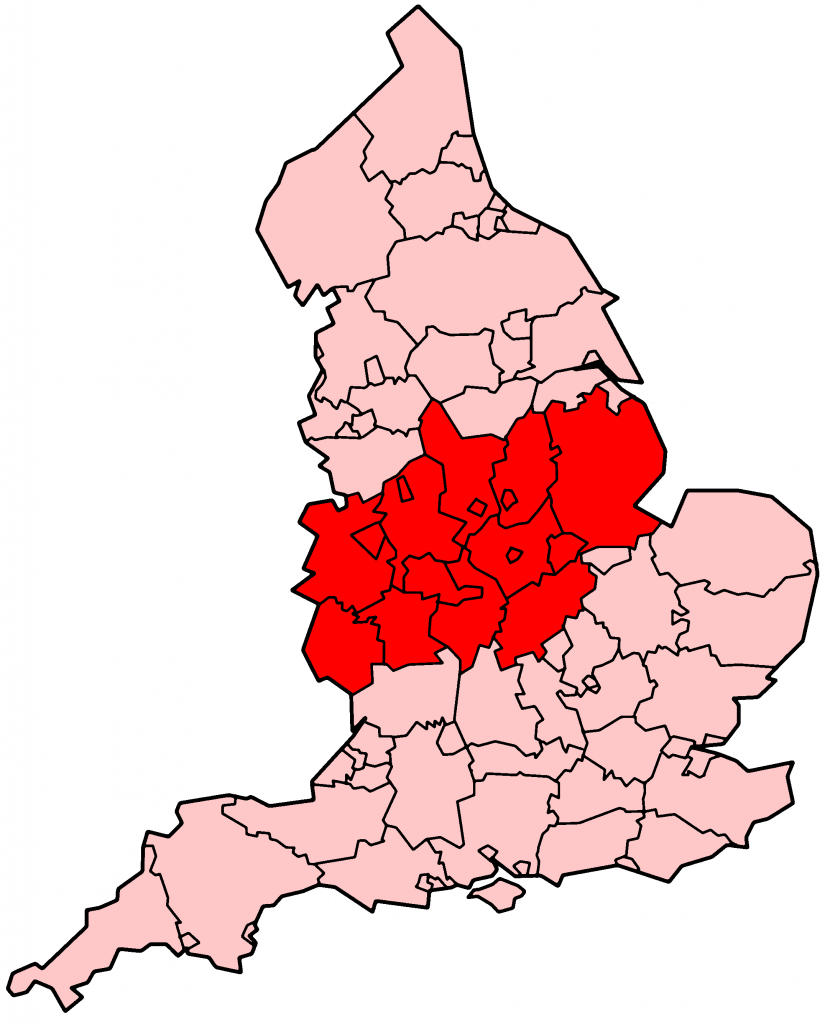

The Midlands, the tight belt keeping in the flab. Photo: Wikipedia.

Author Robert Shore contacted me through LeftLion a year ago about a book he was writing about the Midlands. His central argument is that the Midlands is a forgotten region and all cultural arguments position people as either belonging to the north or south. He was after a local phrase to capture this and I suggested Neither Use Nor Ornament, though he eventually went with Bang in the Middle. I was really intrigued by his book as it was much needed and so I explained, or rather confessed, how the last ten years or so of my life had been dedicated to promoting Nottingham culture and history from creating The Sillitoe Trail to my current project Dawn of the Unread.

A few months ago he got back in contact to tell me the book would be coming out in April (there is a review in the next LeftLion) and that after five years of trying, he’d managed to persuade BBC Radio 3 to commission a series of essays on the Midlands. He asked if I’d be interested in writing one.

I mention this as an important tip to aspiring writers. Most commissions come through people you know. This isn’t nepotism. It’s serendipity. I write for free for LeftLion but through this I get to meet lots of people within the industry. The digested read: You create your own fate.

I pitched various ideas to Robert and we eventually settled on ‘Whatever You Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not’: Arthur Seaton and Nottingham’s Rebellious Individualists. It’s the first time I’ve written for proper radio and had to quickly familiarise myself with the grammar, such as repeating various facts as the listener can tune in at any point. Then there was the usual caution of the BBC, such as recording two versions of a Sillitoe quote (with and without ‘bastard’) as well as explaining who Brian Clough was, just in case someone living in Malaysia was unaware of the footballing genius.

Alan Sillitoe, author of Nottingham’s defining book Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Photo Dom Henry.

It was challenging to write as I needed to talk about Nottingham in the context of the Midlands, due to this being the theme of the collection of essays, while also exploring specific literary history and rebellion in Nottingham. As we have this in abundance I was spoilt for choice, which is some ways made it even more difficult. In the end I took Arthur Seaton as the main narrative thread and interweaved relevant points around him.

The word count for a 15 minute essay is about 2,200 words. Any more and you can’t get in the natural pauses and emphasis. I recorded this in London and had Robert, a sound engineer and the controller for Radio 3 in my earphones offering advice. One piece that was really useful was smile when reading relevant passages as it helps to change the tempo and rhythm of your voice.

I hate my voice and laughed when the controller politely asked if I’d ‘ham up’ the Nottingham accent when doing quotes. Our dialect is notoriously difficult to capture, just look at Russell Crow as Hood and Albert Finney’s Manc Arthur Seaton accent. And did he mean north or south of the Trent? Also, how could I ham up an accent when I’ve lived in Leeds, Manchester, Cambridge and have weird inflections from each? But it was more enjoyable than I thought it would be thanks to some professional guidance. Hopefully I won’t sound too much of a numpty and Al Needham, the master of local vernacular, won’t give me a hard time.

The essays come out around the 24 April. The four contributors are Geoff Dyer, Henry Hitchings, James Walker and Katherine Jakeways. BBC Radio 3 The Essay website