Photograph by random Chinese University of Nottingham student.

Half a century ago, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning became the first Pan paperback to sell a million copies thanks to master gobshite Arthur Seaton. The novel opens with Seaton having a skinful down his local, The White Horse, for no other reason than it was Saturday night, “the best and bingiest glad-time of the week, one of the fifty-two holidays in the slow-turning Big Wheel of the year”. By the end of the evening he’s had a drinking game with a sailor, puked up over a couple of oldies, fell headfirst down the stairs, and ended up in bed with someone else’s wife. It’s no wonder that a councillor at the time wanted the novel banned, fearing it would damage the reputation of Nottingham forever.

But Seaton is more than just your average drunk. He’s belligerent and hedonistic with a healthy scepticism of all forms of authority. Despite only being twenty-one, he’s clocked how the system works, announcing in those flat Radford vowels: “Factories sweat you to death, labour exchanges talk you to death, insurance and income tax offices milk money from your wage packets and rob you to death. And if you’re still left with a tiny bit of life in your guts after all this boggering about, the army calls you up and you get shot to death.”

People often talk about Saturday Night and Sunday Morning as a working class novel, but it’s more nuanced than that. Firstly, this is not a novel about class solidarity and changing your material relations. It’s not us against them. It’s more personal than that. It’s me against them. Seaton is a defiant individualist who lives by cunning and wit. He’s too selfish and too wise to be a member of anyone else’s gang, he’s out for himself – all the rest if propaganda.

The novel is set during the transformations in postwar Britain faced by a more affluent society. Seaton was well paid for his graft, earning more at his lathe than a footballer at the time. He could afford nice clothes, drink himself senseless, and go out for the whole weekend. This is one reason why the novel wouldn’t work today. The working classes have been replaced by an atomised and powerless underclass. The system has become a lot cruder: there are those with money and those without. Manufacturing and overtime have been replaced with call centres and zero-hour contracts. The most you can hope for on a Saturday night now is to be able to fill the car up with petrol. If you’ve got a car…

Seaton is a product of his environment. He is not an ‘angry young man’ but someone trapped in a world where violence is just a part of everyday life. Husbands attack their wives and the wives attack their husbands. Men eye each other up in the pub and shaft each other at any opportunity. Tonally Sillitoe captures this through negative adjectives so that the sun smacks you in the face, the grass is flattened when you walk on it and tenderness is shown by grabbing the hand of the woman you love. Only an uneducated writer who’s not been on a creative writing course could cobble together such wonderfully claustrophobic and aggressive prose. You won’t read anything this raw again.

Sillitoe wrote that Arthur Seaton “has no spiritual values because the kind of conditions he lives in do not allow him to have any”. The problem is not an ‘angry’ author or a selfish character. It’s society itself. It’s for this reason that I think it’s more accurate to describe Saturday Night as an existential novel in which Seaton eventually concedes “everyone in the world was caught, somehow, one way or another, and those that weren’t were always on the way to it”.

All the factories in Nottingham have gone, as have the local pubs. Indeed, recent research published in the medical journal BMC Public Health, revealed that the proportion of 16 to 24-year-olds who do not drink alcohol has increased from 18% in 2005 to 29% in 2015. Yet we still love the hard drinking, womanising Seaton and crave his antics fifty years on.

Photograph by: Sybille Nieveling

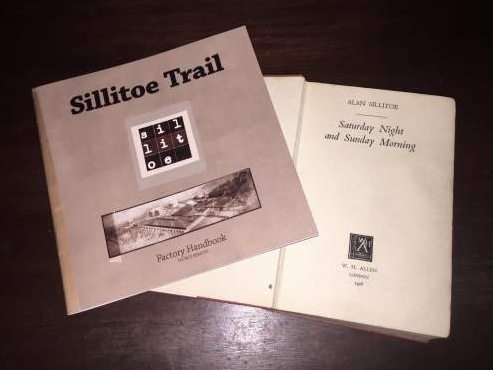

This weekend, four journalists from a Swedish Food Workers Union’s magazine who are interested in working class literature came over to interview me and to discuss The Sillitoe Trail. We took a literary walk across Radford, tracing the perimeter of the old Raleigh factory which is now part of the University of Nottingham’s Jubilee Campus, ending up in Seaton’s old watering hole, The White Horse (now a curry takeaway).

The world Sillitoe described is radically different today, but the charismatic Seaton remains as appealing as ever. His defiant individualism and personal credo of “I’m me and nobody else; and whatever people think I am or say I am, that’s what I’m not, because they don’t know a bloody thing about me” kept our conversation going for hours as we imagined how he would deal with Brexit (one less boss to worry about, another form of propaganda) and other contemporary issues. And this is the wonderful thing about literature, it has the power to bring random people together. It creates communities – the very world that Saturday Night describes, the very world that has disappeared.

This article was originally published by Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature

About: James is currently working on Whatever People Say I Am and D.H. Lawrence: A Digital Pilgrimage. He has used the persona of Arthur Seaton to argue it’s Time to Ditch the Traditional Essay in the Journal of Writing in Creative Practice.