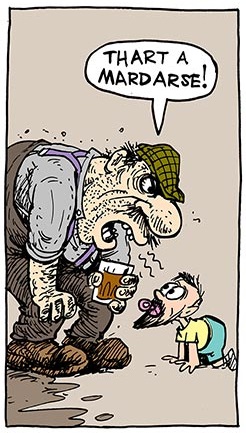

Artwork: Dawn of the Unread

A few years ago I wrote a 15 minute essay for a BBC Radio 3 series called In Praise of the Midlands. It was pretty straight forward. I banged out 2,000 words on the topic of The Defiant Individualism of Arthur Seaton, made a few tweaks over email with the series producer Robert Shore, booked a studio and read it out. Then I did some vox pops for a BBC Radio 4 series called Made in the Middle. Both were Made in Manchester productions and creative director and founder Ashley Byrne asked me to pitch other ideas. Although I was really interested, I didn’t have time. I was balancing two jobs and every other waking hour was spent cobbling together Dawn of the Unread or doing Notts propaganda for LeftLion.

After three years of hard slog Dawn of the Unread got a full stop of sorts when it was published as a physical book by Spokesman Books in 2017. In March last year I jacked in LeftLion after 13 years of blathering on about all things Notts. Ashley, forever patient, got in touch again and I pitched the idea of exploring pit poetry in the East Midlands. A year or so later and it’s going to be broadcast this Sunday on BBC Radio 4 in the three part series Tongue and Talk: The Dialect Poets.

The series kicked off on 13 May when Catherine Harvey returned to her roots in the North West of England to see if the dialect poetry of the cotton mills of the 19th century is alive today. In episode two, I explore a bit of the Notts accent and then have a natter with retired pitmen still reciting their dialect poetry in venues across Nottinghamshire. The final episode sees Kirsty McKay return home to Northumberland only to discover the erosion of dialect and culture by the encroachment of urbanisation and influx of people moving into the area.

David Amos (cap) and me (scruffy get in brown jumper) being recorded by Ashley Byrne at Breach House (DH Lawrence’s childhood home)

I’ve blogged the arse out of the content of the episode for various websites (see related reading) so I thought it would be useful to share a few of my experiences of writing for radio. The most difficult thing about writing an episode that involves interviewing lots of people is that you’re blind to the process. On this page I can see my thoughts in words. I can delete things and go back to earlier drafts. But I can’t see audio. The editing down of the interviews was done by the internal producers at Made in Manchester. I produced a script with fillers and suggestions of where interviews should go, but ultimately I was working blind. Writers aren’t used to trusting other folk. We write because we’re greedy and we want control. So letting go is difficult, but not when you trust those around you.

Ashley explained that sometimes the writers get to listen to the audio and suggest the bits of gold they want included. But because this was my first time, and we had a bit of a tight deadline, they did the editing. I then received various We Transfer edits of the work in progress. Given that we easily recorded over 10 hour’s footage, how on earth were they going to get it down to 27 minutes and 36 seconds long? It was a headache I was pleased to avoid.

I think we did four recordings in the studio, gradually chipping away at fillers. Then as we neared completion it was a case of reading out multiple introductions of guests to ensure our verbs covered the three tenses: past, present, and future. This typically included rattle such as: Next up is…Later we will be talking to…We return to…Our next guest…etc. The last thing you want is to get a call when you’re on the lash asking you to get to studio pronto just to say ‘And now we have’.

It’s obvious but it’s worth stating: Recording on location means there are different noises, echoes and nuances in the recordings. So ensuring consistency for the fillers was vital. This also threw up some challenges as I sometimes had to think up things off the cuff rather than having the luxury of contemplating thoughts in Word. Different medium, different rules. Fortunately I was in the very capable hands (or rather voice) of Iain Macknes, Made in Manchester’s Head of Production. Iain also gave me some really good advice. He told me to try and sound friendlier. To remember the programme was going to be broadcast in front rooms and kitchens while couples washed up. I was barking a bit at the beginning, perhaps laying too much emphasis on the flat Radford vowels of Arthur Seaton, speaking as if I expected to be attacked. This is odd because my voice is naturally quite quiet. I think because the programme meant a lot to me, in that I had a responsibility to Nottingham to do a good job, I was drilling out words so that they left my mouth as concrete, something that no listener could break.

When we were recording on location I worked with three different people. This was simply a case of who was available at the time. Each person had their own technique and tips, although all of them were keen to record doors being opened, footsteps across paths, and live location introductions. I was advised by Ashley in one recording to repeat certain words as someone was talking as this reminded listeners I was there and conveys interest. But I didn’t like this as much because I tend to laugh a lot and so it sounds like I’m laughing at people when I repeat what they say. But this might be my own paranoia. Hearing your own voice is really weird. I’m a bit more used to it now after doing The Nottingham Essay series on YouTube, but I don’t like it. Feels like I’m in a David Lynch film.

Norma Gregory (L) Lord Biro (R). Photos on left by James Langtry. Photo on right by JW.

Catherine Harvey was the series producer and so was tasked with ensuring consistency among the programmes. This meant ensuring we kept a good beat between poems – it is a poetry programme after all, and explaining dialect. Then of course there’s the BBC who have their own rules and regulations. Overall this meant we didn’t get the full force of Al Needham’s bawdy irreverence, and we also missed out on Lord Biro’s memories of the Strike. I had a really interesting chat with Norma Gregory about her research project Digging Deeper: Coal Miners of African Caribbean Heritage but we were unable to use it in the end as the emphasis of the programme was poetry and dialect. I’m hoping to make this available on soundcloud at some point.

I’m really pleased with what Made in Manchester have done and I’m really grateful that Ashley Byrne has shown faith and pestered me to do summat. There are a few things that I would like to change given a bit more time, but the story has to end at some point. Writers never learn this lesson. That’s why we keep telling the same story over and over again. I guess my story is Nottingham. Perhaps it’s time I moved somewhere else.

Talk and Tongue: The Dialect Poets is broadcast at 4.30pm on Sunday 20 May

RELATED READING

- Made in Manchester – madeinmanchester.tv

- Nottingham Dialect and Mining Culture Documentary to be Broadcast on BBC Radio 4 – LeftLion.co.uk

- Tongue and Talk: DH Lawrence and dialect – thedigitailgrimage.wordpress.com

- #TalkandTongue Pit poetry and Notts dialect dawnoftheunread.wordpress.com

- Tongue and Talk guest blog writingeastmidlands.co.uk

- Language, mining and poetry ntu.ac.uk

- Digging Deep (Norma Gregory) blackcoalminers.com

- Talking Notts on wireless nottinghamcityofliterature.com

I hope that I am contacting the raight bloke who hosted the “Tongue and talk” on R4 yestdi. If so, yo can guess ah’m a neast midlander.

Back to RP.

I was born in Langwith Junction, a railway village in north east Derbyshire, about a quarter mile from the Notts border, my dad, granddad, uncles and cousins were all “Pit moggies”in one or the other county, so I was subject to both county’s style of speech, our nearest biggish town being Mansfield or Manzfild. As exemplified in the expression ” It’s like gooin rahnd Waahsup (Warsop) ter get ter Manzfild “! A local translation of going the long way round. In your piece, the term “sorry” was quoted, this could replace duck or yewth and sometimes pronouced “serry”, as in “serry ahr, ahr it is tho ” meaning you are correct. By the way in those far off days, a moggie was a mouse and a cat was a moggie catcher. There was a legend about one variation of speech called “Wooduss chinese” as exemplified by this conversation overheard on a Manzfild Districk bus. “Ooo woshi wi? Woshi wi im or woshi wi ersenn?” Translated as “Who accompanied the female in question? Was she with her husband/boyfriend/significant other? or was she by herself?” Wooduss = Mansfield Woodhouse. Another expression involving Warsop was “Does tha cum fra Waahsup?” meaning “you have left the door open”

Ah’ll sithy yewth.

Wilf.

As a child of the 1930s, when he heard of my birth, the king straightway abdicated, I am amazed at what I can remember, frinstance my dad’s lamp check was 1109. We lived with my granddad Ammon, in a terraced house, 15 Langwith Junction, our address changed 3 times without us moving, and ended up as 111 Langwith Road. There were 6 inhabitants in the 30/40s, Granddad Ammon, our dad Fred, our mam Anne ( known locally as Nance), elder brother Geoff, elder sister Anne and the baby, me. A problem arose when our sister began to develop certain features, meaning bath times had to be timetabled as we did not have bathroom and bathing was carried out in the living room (or house) in front of the fire with hot water ladled from the side boiler, cold water carried from the kitchen. As the youngest, I was last in the (used) water. To avoid the congestion, Geoff and I would go on Saturday afternoon to Shirebrook pit, Dad’s workplace and meet him at the pithead as he came off shift, then go to the pithead baths for a shower, along with lots of other mineworkers, all with black faces, just imagine the uproar if that happened these days !!! Dad also was adamant as to our careers by declaring “If I catch you in this yard looking for a job, I’ll kick your arse till your nose bleeds !” He had a way with words, me dad. He made sure that we all went to grammar school. He was pleased when we both got jobs involved with computing. My 26 year experience involved in academic computing leads me to propound the following thesis :

I’m not a Facebook user,

Neither do I tweet.

I email, write or phone folk,

Or face to face we meet.

There’s one thing about Twitter,

The title aptly fits,

Majority of users

Are downright flippin’ twits

Hi James,

I’m Owen Watson’s grandson and came across the Talk and Tongue Radio 4 piece by accident when one of my friends said she’d heard his name on the radio yesterday in connection with pit poetry.

I’ve listened to the programme and to say I’m surprised and proud is an understatement. He died in 1980 and I was only 7 at the time, but I have very vivid memories of him and our walks around Shipley Park every Sunday afternoon.

He was a great naturalist and artist and I’m sure that my love of natural history comes from our walks in the countryside at a formative age. He was an expert at identifying bird song, which species of fungi were edible and which were poisonous and seemed to me to have an encyclopaedic knowledge of the natural world.

Thanks for keeping his memory alive. I’m sure he’d be surprised and delighted to be featured on Radio 4 and I only wish his wife Alice and my Mum and Uncle Les were alive to hear it.

Thank you once again!

Best wishes

Richard Buxton

Hi James,

I happened to catch your show on Radio 4 this week. I just wanted to say hi, I grew up in Cotgrave too and it was great to hear your work.

I think the Nottingham accent is very underrepresented (outside of Shane Meadows’ films) and it was great to hear the poetry too.

Thanks!

Christina

Hi James,

Just listening to your Radio 4 documentary (I know I’m really late to the party!) and I just wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed it. Really interesting and informative – and the focus on the accents and dialects of Nottinghamshire was wonderful! So nice to hear so many gorgeous non-RP voices on the BBC. Your presenting style was really great too – you’re a total natural! Congratulations on a great programme.

Best wishes

Leanne