In November 2020 I gave a talk to the London Group of the D.H. Lawrence Society about progress of the D.H. Lawrence Memory Theatre. This is a project that Paul Fillingham and I have been working on for five years or so now. But the main purpose of the talk was to discuss the best way to celebrate heritage. This is a subject I’m very passionate about. Here’s a couple of examples of how it can go horribly wrong.

Culture imposed from above

Culture that’s imposed from above can cause antagonism and resentment. An example of this would be a sculpture plonked into a community with little consultation or awareness of those left to gawp at it every day. Instead of inspiring individuals, it becomes a totem of discontent: ‘the money would have been better spent cleaning up graffiti’; ‘they could have built a playpark for kids’, etc. An example of this is Jean-Pierre Raynaud’s Dialogue with History (1987) which attempted to commemorate the arrival of French settlers to Canada through a series of white cubes but looked like a Rubik’s Cube with the colour stickers peeled off. Nicknamed the toilet, it was criticized for failing to fit in with its 18th century surroundings. It was flattened in 2015.

Vanity projects for the artist

Some heritage is so divisive that discussions focus on the artist rather than the subject. An example of this is Maggi Hambling’s naked statue of feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft, author of the A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). It is appalling. Can you imagine someone commissioning a naked statue of Winston Churchill or Oliver Cromwell? Of course not. It wouldn’t happen. Hambling argued that her Silver Surfer statue wasn’t meant to represent Wollstonecraft, rather it’s for her. “Clothes define people,” she said, “As she’s Everywoman, I’m not defining her in any particular clothes.” But she’s not everywoman. She is slender, well- toned and perfectly formed. She is drawn from the male gaze, reinforcing the perfect body types that have oppressed women for decades. In terms of arousing public disgust, it is more offensive than Vasile Gorduz’s naked monument to Romania’s stray dogs, which is quite a feat…

The same old same old

Blue plaques and statues are great for selfies but rarely serve their purpose –capturing the spirit or essence of the person they claim to be celebrating. There is also a danger of over celebrating the life of a famous individual, and this is a problem I have with D.H. Lawrence’s birthplace of Eastwood.

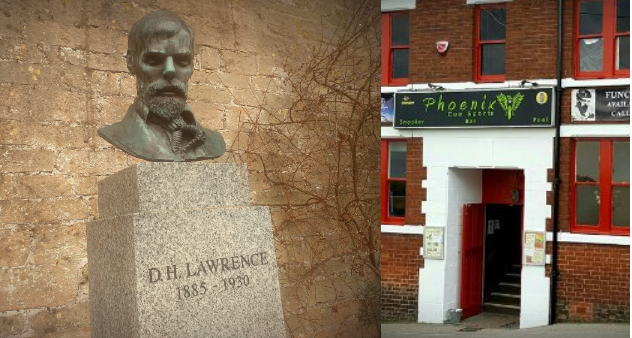

Eastwood is in danger of becoming a Disney Park to Lawrence. Café’s, the Rainbow bus line, the Phoenix snooker hall, the local Wetherspoon, all bear some relation to his life and work. Some of this is done well, others not so. It must be suffocating for the locals to be constantly reminded of the man who couldn’t wait to get away from the place they are all stuck in during lockdown.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s great that we are celebrating our literary heritage and the Midlands should definitely aim for an equivalent of Bronte country or Hardy’s Wessex. But I just don’t think another statue will do it li– the idea banded about by each new incoming Broxtowe MP. I explained why in a recent talk via Zoom to the London branch of the D.H. Lawrence Society.

Literary heritage requires imagination. D.H. Lawrence was a writer who was, according to Geoff Dyer, ‘nomadic to the point of frenzy’. He never settled in one place for more than two years and never owned any property. Despite this, heritage determines we render him static in perpetuity. If we are to celebrate Lawrence’s life, we need the form to reflect the content. We need something mobile, not static. This is the rationale behind the D.H. Lawrence Memory Theatre. It is a moveseum if you will; a travelling art exhibition modelled on Lawrence’s personal travel trunk, that curates Lawrence’s life through artefacts. It will retrace Lawrence’s steps across Europe and beyond, if and when we ever send Covid packing…

This project is not imposed from above but from within. It is a conversation. We want to create a space for many voices to think through the life of this contradictory and complex character. One artefact I want to include in the memory theatre is rage and so the talk helped generate reasons for Lawrence’s rage as well as ways that we can represent this as an artefact. You can read more about the talk in Catherine Brown’s review here.

This blog was originally published as ‘How to celebrate heritage when your subject is ‘nomadic to the point of frenzy’’ at The Digital Pilgrimage on 13 Jan 2021

Further Reading

- James Walker’s Memory Theatre talk to London Group of the D.H. Lawrence Society at catherinebrown.org

- ‘Insulting to her’: Mary Wollstonecraft sculpture sparks backlash at theguardian.com

- The 10 Most Hated Public Sculptures at artnet.com

- The role of community in the creation of value: the contribution of Stakeholder Theory at theaxiologicalperspective.wordpress.com

- The D.H. Lawrence Memory Theatre at memorytheatre.co.uk

- D.H. Lawrence is all the rage at torpedotheark.blogspot.com