Rick Gekoski’s Guarded by Dragons: Encounters with Rare Books and Rare People is an illuminating insight into his fifty years of experience buying and selling rare books. The opening chapter reveals how D.H. Lawrence kickstarted his habit…

Rick Gekoski published his first novel, Darke, at the age of 72. But he is perhaps best known for his half a century selling rare books. As the title of his memoir suggests, the treasure he seeks is scarce, carefully buried, and ferociously guarded. But is he himself a dragon, guarding rare books he’s accumulated, or a heroic slayer? It would seem the latter, because once you’ve got the treasure, you want to trade it in for more. His is a life very much focused on the journey rather than the destination.

A rare book dealer requires two basic skills: to know when a book is buyable and when to sell it for a higher price. The best way to accumulate this knowledge is to serve an apprenticeship in a bookshop. He didn’t. He entered the rare book world as an academic and a collector. Thus, he becomes frustrated at conferences when young collectors demand he pass down trade secrets. But there is no elixir. Knowledge can’t be passed down. All you can do is go slay your own dragons and see what happens.

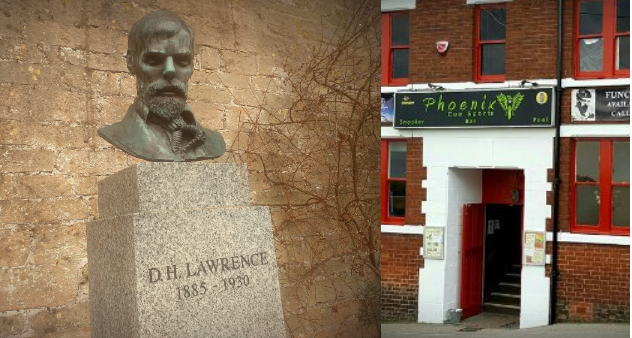

This ethos of experience shapes his memoir. Over thirteen chapters we see him play ping pong with Salmon Rushdie, upset a Poet Laureate, and get dragged through the law courts on more than one occasion. But in terms of my own research, I was reading this for the opening chapter ‘On Sabbatical with D.H. Lawrence’.

It’s late 1974 and the Gekoski’s and their newborn baby are on a first-class plane to New York to see his ferocious mother who is dying of cancer. He’s taken a much-needed sabbatical and ‘wangled’ a contract with Methuen for a critical book on Lawrence. The problem is, he doesn’t have the energy for sustained academic research. What he enjoys more is collecting the first editions he’s been accumulating for the research he has no intention of finishing. It’s all very Dyeresque – something he alludes to.

Research, however, provides him with the excuse to leave his pickle-eating baby with his wife while he visits a secondhand bookseller called William Hauser. ‘Bill’ is nearing retirement and flogging off his books at bargain prices. He visits him five times and the books get cheaper on each visit. We learn that price is not just determined by the value of the object, there are other variables at play. He pays £41 for 12 books and sells most of them, over the coming years, for £333. This would make him a dealer. But as he invests this in more acquisitions, he is also a collector. The fact that he has the books shipped over to Blighty – so that his wife doesn’t find out what he’s been up to – suggests he is either a shrewd businessman or a bit deceitful.

In 1975 books were cheap but hard to find. For example, unable to procure his own copy of Warren Roberts’ Bibliography of D.H. Lawrence, he photocopies it from his university library and then annotates it with his acquisitions – who he bought from, who he sold on to. He explains that ‘unlike work on the putative critical book, which was glacially slow and unenthusiastic over these years, my collecting was focused, passionate and highly organized.’

He becomes obsessed with Lawrence, detailing all his books sold at auction. Later, he convinces his bank manager to allow his to go further into the red so that he can acquire a collection of Lawrence books from an antiques dealer in Wales that include some rarities, such as signed first editions of Lady Chatterley. The dealer insists on being paid in cash.

Allow me a quick digression. During lockdown, I went a year and a half without drawing out cash. Everything went on my card. Then I went to Yorkshire to visit some relatives. First a pizza take-away in Pateley Bridge refused to accept card and pointed to ‘machine across the road, mate’. Then the following evening, a Thai takeaway would only deliver if we had £42.32 in cash. As a sweetener, they threw in two free bottles of Singha beer and would deliver in 25 minutes.

Back to the dodgy dealer.

The dealer gives firm instructions to meet him at a train station at 12. He hangs up before checking if this is convenient. ‘He knew I was keen’ explains Gekoski ‘and may well have known that university lecturers have a lot of free time’. Of course, he can’t resist. But takes a friend along with him just in case. The meeting is fraught with danger, but it’s worth it as the dealer’s collection includes some proper treasure, such as Bay – A Book of Poems, published by The Beaumont Press in 1921 and sold in three issues: 500 copies, 50 signed copies, 25 signed copies bound in vellum.

It’s at this point, after he’s been bundled into the back of a car, that he confesses that writers, collectors, raconteurs make ‘our stories smoother, funnier, more revealing’ because it makes for a better story. He is guilty of ‘unconsciously constructing a faux narrative in which I braved dragons, confronted a dragon, returned safely from the hunt with my treasure: a hero, of a modest sort’.

Gekoski may be an unreliable narrator but he’s certainly a compelling one. I only intended to read the opening chapter to get my Lawrence fix but ended up devouring the entire book in one sitting. In doing this I’ve gone on to discover that John Fowles was anti-Semitic and that John Updike had to explain what a blowjob was to Victor Gollancz. All of which, to use an Alan Sillitoe quote, is ‘cheap gossip for retail later’. Wonderful stuff.

This book was kindly leant to me by David Belbin, Chair of Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature. David is also a writer and a collector of first edition books. This blog was originally published on The Digital Pilgrimage here

Guarded by Dragons is available in HB for £18.99 from Constable at hachette.co.uk

Further Reading

- Rick Gekoski’s website gekoski.com

- Review in the FT ft.com

- Review in The Irish Times irishtimes.com

- Review in The Spectator spectator.co.uk

- Review in Fine Books Magazine finebooksmagazine.com