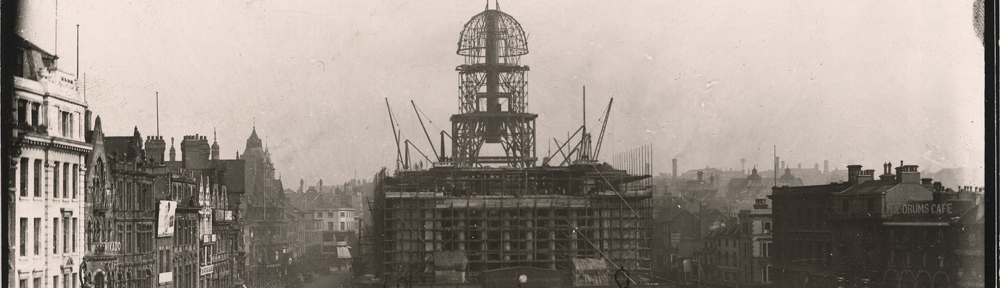

Get drooling…An artist’s impression of how the new Nottingham city centre library will look. See https://www.mynottinghamnews.co.uk/

Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature and the City Council are forming an innovative partnership to ensure the construction of the new Central Library has the potential to raise literacy levels, position the library as a focal point of the community, and build upon Nottingham’s rich literary history. These are issues very close to my heart. When I created Dawn of the Unread, a literary graphic novel exploring Nottingham’s literary history, it was very much a love letter to libraries and the potential of books to transform lives. Therefore, I was ridiculously excited to join in a consultation event hosted by Sandy Mahal and Nigel Hawkings at NTU. Here’s my top 5 wish list…

You and Mee (or Mee time or Mee, Myself and I or You get mee, etc)

Arthur Mee (21 July 1875 – 27 May 1943) is best known as the author of the Children’s Encyclopædia and The Children’s Newspaper, the first newspaper published for children. Born in Stapleford, he earned money as a teenager reading the reports of Parliament to a local blind man. All of which makes him perfect to be featured in some capacity at the library. In terms of literacy, teenagers could be encouraged to produce their own newspaper (digital or physical) to build on his legacy, possibly to be overseen by the Young Ambassadors. Or he could simply be recognised within the library in the children’s reading area ‘You and Mee’ as a means of cementing Nottingham’s rich history of encouraging young people to read.

The Human Library

The Human Library® is a brilliant concept whereby readers loan out humans and have conversations they would not normally have access to. The organisation was created in 2000 to create dialogue around difficult subjects. A variation on this (or partnership) could see skill-sharing sessions to help improve literacy levels. For example, specialists could lend their skills (I’m James and I specialise in producing digital heritage projects, loan me for 30 minutes for support on your ideas) or library users could request specialist ‘books’ (people) which could be sourced. Imagine young people actively seeking information on knife crime, difficulties at home and how to deal with them, help with homework, finding friends. The potential is massive. Given this organisation exists they would need to be consulted and partnered with.

Digital screens/Tik Tok

I recently visited Krakow, a fellow UNESCO City of Literature, and in one museum was a 360 degree screen telling the history of the city. A similar screen at the library could have multiple purposes in commissioning new work (which could address particular themes) as an information space, or to project new creative work self-generated by locals. One medium which would work well here is Tik Tok which is basically a 15 second platform that acts as a stage and positions the audience as performer. Content is quick and easy to create on your phone, feeds off of meme culture, and enables creative expression that is relevant to younger people. There is potential to curate ‘best of’ sessions, again possibly run by the Young Ambassadors. A good starting point for ideas would be Nick Robertson, the BBC’s social media content producer who was discovered making snapchat videos about his life working in Starbucks. The fact that all people above 30 will probably hate this medium is the exact reason it should be embraced.

Library App

Now is the time to bring the library card into the 21st century with an app that enables users to visualise their reading history. Whether we like it or not apps provide simple ways of monitoring and motivating behaviour. A FitBit tells you how far you’ve walked, Netflix algorithms tell you what to watch next, etc. A library app could perform similar functions and act as a digital guide. I’ve been teaching a module at an international college for 10 years where I get students to design a mobile app. Overwhelmingly 85% of them come up with an app that shows them how to do things… There is also opportunities or partnerships here with Vue cinema in the neighbouring Broadmarsh Centre. When you get out your first six books, you get a free cinema ticket…

Confessional booth

I’ve used booths before in various projects such as the East Midlands Heritage Awards and they always work because people love talking one to one. A digital booth in the library would allow readers to share their favourite books or characters. These could be projected onto digital screens, linked to an app, or simply viewed in the booth. This idea builds on the readers recommendations you see in places like Waterstones. But more importantly it shows young people that their opinions and ideas are valued. It is one of numerous ways to build an inclusive community.

James is currently working on Whatever People Say I Am, a graphic novel serial challenging stereotypes, and D.H. Lawrence: A Digital Pilgrimage, a memory theatre exploring Lawrence through artefacts.

This blog was originally published on the Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature website on 9 March 2020. You can subscribe to their newsletter here.