Ai has appeared out of nowhere and promises to solve every ‘problem’ for the creative industries from writing fiction to creating award-winning photos to producing videos. The narrative underpinning the solutions is one of ease and convenience, but it also removes process, context and knowledge. Although there are many benefits to Ai I fundamentally disagree that progress should be defined by speed and have outlined the arguments for why delayed gratification is important to creativity in the latest issue of Viewfinder 122 – a publication that focuses on the moving image and sound in education.

Firstly, we learn through practice. It is in doing things that we acquire knowledge. In education this is referred to as active learning. To strip away this experience and get Ai to do all of the work for you is to make your brain redundant. There’s a lot of bullshit doing the rounds about how the skill is in the instructing of the Ai but let’s not confuse this with autonomy or creativity. It’s like saying you do all of the washing because you’ve poured conditioner into the Hotpoint and pressed 40 degree spin cycle.

Secondly, we develop skills through practice, and this encourages finesse. For example, when I made my first Locating Lawrence video on YouTube I recorded my audio and added images. Then I began to add sound effects for emphasis. Now I do all of these things and select a relevant fade out track. The June 1923 video ends with D.H. Lawrence declaring ‘we have to be a few men with honour and fearlessness, and make a life together,’ so I added the opening chords of ‘Eye of the Tiger,’ the theme tune to Rocky. People of a certain age will get this, and it adds another layer of meaning to the video. Others won’t get the reference but can enjoy the video for its content. The point is that producing work each month creates the desire for improvement and experimentation. With Ai you just press enter.

Lastly, it is in searching for relevant images to accompany the audio that knowledge is acquired. This month I discovered that Lawrence was reading Soeur Philomene (1890) by the Goncourt brothers. I did some further research and found that Edmund and Jules Goncourt were unique siblings in terms of literary history in that they wrote all their books together and did not spend more than a day apart in their adult lives, until they were finally parted by Jules’s death in 1870. I would not have discovered this if I had let Ai to do the work for me. Research creates intrigue. Intrigue creates knowledge. Knowledge creates wisdom.

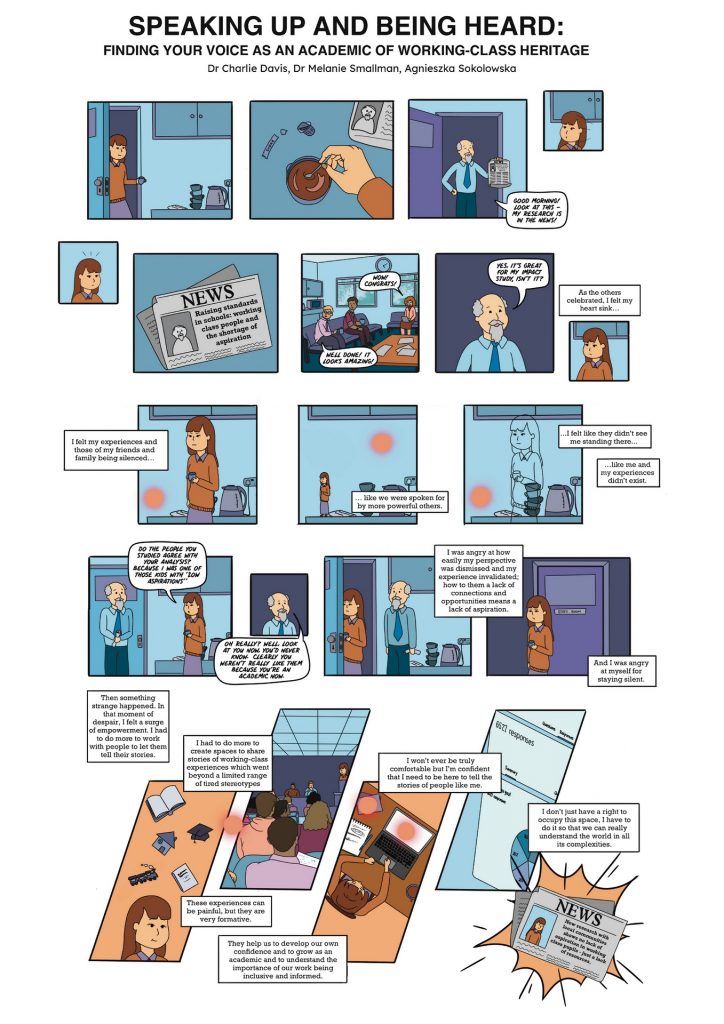

My career as a digital storyteller involves finding innovative ways to explore literary history and tell stories. As an academic, I have introduced new assignments to modules, such as visual essays (see above), so that students can embrace serendipity and discover new and interesting facts through their research. I want them to struggle and get frustrated so that they can feel the elation that comes with the finished output. Ai removes these fundamentals of what it is to be human; we should be concerned. But, as is always the case, this is down to the individual. If you want the immediate gratification and glory of something else creating something for you, go ahead. But if you want to push yourself to the limits, embrace the process and marvel at your creativity – while you still have it.

Related reading

‘The Importance of Delayed Gratification: D.H. Lawrence and the Visual Essay’ in Viewfinder 122: May, 2023

‘Rethinking Literary Heritage and the Traditional Dissertation’ in Makings Journal (Studio), May 2022

‘How Best to Celebrate Literary Heritage?’ in Journal of D.H. Lawrence Studies (JDHLS) Vol 6 (1) 2021

ViewFinder newsletter mailchi.mp/learningonscreen.ac.uk/viewfinder-the-digital-humanities