I was approached by the Guardian Travel Editor Andy Pietrasik to write a piece on literary Nottingham for the 2 Feb issue. This work probably came about through The Space. I was encouraged to write a ‘personal’ account and managed this second time around after being sent a useful link on a Larkin walk as guidance. This then went to a fact checker to clarify a few dates. I’ve included the original article below as I’m always intrigued by the editorial process and what does and doesn’t eventually go in.

I was approached by the Guardian Travel Editor Andy Pietrasik to write a piece on literary Nottingham for the 2 Feb issue. This work probably came about through The Space. I was encouraged to write a ‘personal’ account and managed this second time around after being sent a useful link on a Larkin walk as guidance. This then went to a fact checker to clarify a few dates. I’ve included the original article below as I’m always intrigued by the editorial process and what does and doesn’t eventually go in.

Tell somebody you’re from Nottingham and they’ll either respond that it’s a dangerous place or that you’re a lucky swine because the ratio of women to men is 4:1. Let’s quickly clear this up. The female myth is a throwback to the lace industry but quite convenient for tourism as it means we get tons of stag nights turning up expecting to find the streets paved with garters. As for a dangerous place to live, you couldn’t be further from the truth. It’s not possible to be a threat when you call everyone “me duck” in a camp accent.

It’s at this point I correct the stags and inform them it’s actually 10 women to every man and I’ll show them where they’re all hiding out if they get the beers in. They could be lurking down in the sandstone caves that run beneath the city which, 700 years ago, acted as an underground malting system, enabling us to brew beer all year round and helped cement another of our perceived characteristics, that of big drinkers.

Our bachelors are suitably intrigued so I convince them to hop on a 28 bus into Radford, home of the hard-drinking and womanising Arthur Seaton, the anti-hero of Alan Sillitoe’s 1958 novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, who, like our stags, was “out for a good time and all the rest is propaganda”. But if Arthur Seaton were to fall down the stairs of The White Horse (313 Ilkeston Road, NG73FY) in 2013 it wouldn’t be because he’d just necked 11 pints and six gins as he does in the novel, because now his favourite watering hole is an Indian café. Shisha anyone?

The pub was always the perfect location for ‘angry young men’ and for 40 years was the home of the Radford Boys Boxing Club. The Club played a vital role in the local community by keeping kids off the street and ironically, off of the booze, paying only a nominal fee to the brewery for rent. A luxury the new owner Rasib Khan couldn’t offer when he took over in 2009. Inside it as bland as any other café but the exterior has retained its original features of green Art Deco tiles which make for a beautiful photograph for those wishing to freeze time.

In the late 1950s in which the novel is set, Nottingham was very much a factory city with the likes of Player’s cigarettes, Boots the chemist and Raleigh bikes. These massive local employers created mini towns in Lenton, Beeston and Radford and with it a real sense of community. Workers could go on a pub crawl to quench pay-day thirst without once leaving the estate and everyone, literally, knew your name. But Seaton’s old employer Raleigh closed their Radford factory in 1992 and it has since been replaced with the University of Nottingham’s Jubilee Campus and student flats (Sillitoe Court). Other pubs have gone too, meaning there’s little chance of emulating a pub crawl now.

The landscape may be changing but the spirit of defiance is as strong as ever, captured by Arthur Seaton’s personal credo of “don’t let the bastards grind you down”. These sentiments have particular resonance in Old Market Square which has witnessed our Mayor flattened by cheese in the infamous cheese riots of 1766, and in 1811/12 housed demonstrations by unemployed framework knitters. Their cause was taken up by Lord Byron, a local whose radical maiden speech in the House of Lords attacked plans to make the breaking of weaving machines a capital crime: “Will you erect a gibbet in every field and hang up men like scarecrows?” he asked. I shake with pride as I utter these words but the stags dismiss it as alcohol-induced tremors.

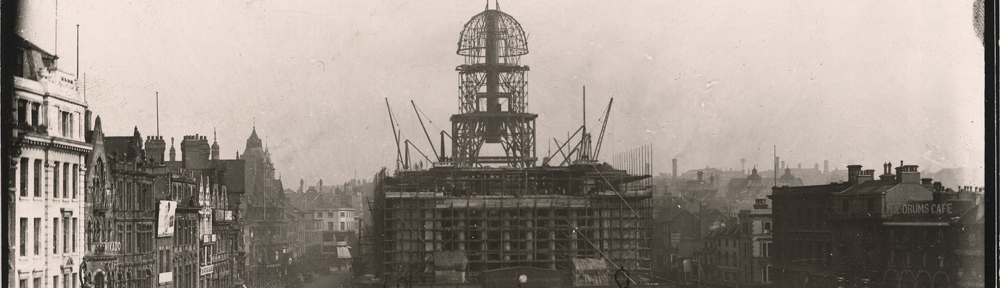

The Square is also home to a multitude of different architectural styles, thanks to Alfred Waterhouse, Thomas Chambers Hine and our very own Watson Fothergill, each producing elaborate buildings in the 19th century to meet the expansion generated by increasing industrial output. But I don’t tell our stags this. Instead I tell them to check out the nearby statue of Cloughie, the self-proclaimed ‘Big Mouth’ who everyone has a story about. He may have put Nottingham on the map through back-to-back European trophies but we love him for his unpredictability and acerbic wit.

Although Nottingham has a history of confronting authority we’ve never been particularly good at standing up for ourselves but this finally looks to be changing through the City Council’s ambitious plans to re-establish the medieval moat and bridge at the 11th-century castle and rebrand Nottingham as the Rebel City – certainly an improvement on the Slanty ‘N’ logo of 2005.

Let’s just hope their definition of rebellion extends beyond men in green tights and taps into our rich literary heritage. With Byron, DH Lawrence, Stanley Middleton and Sillitoe behind us we’ve got plenty to be proud of. We’re a small city and need to use this to our advantage by working together, demonstrated by the forthcoming Festival of Words (9-24 Feb) which has seen lots of local organisations give up their free time to celebrate the one truism we need to build our reputation on: a city of stories.

Download the Sillitoe Trail from the Sillitoe Trail website

Festival of Words website

I enjoyed your article in the Guardian about Nottingham’s literary heritage, and wanted to contact you about it, as it doesn’t include anything about Nottingham’s proud connection with a pioneer in children’s fiction, Geoffrey Trease (although I see from your blog that this was intended as an article on your personal literary connections, so perhaps you don’t know Geoffrey Trease’s works!) Trease was born in Nottingham and lived off the High Street, I believe, as his father was a wine merchant with cellars in the caves. He went to the High School before going to Oxford, which he left before taking a degree because it was boring, to work in a London settlement, and later became a full time writer. He was a pioneer in several ways: following the very distinct division between girls’ books and boys’ books in the Victorian period and the first part of the twentieth century, he was one of the first to write books intended to be read by both sexes, and with mixed groups of main protagonists. He was also one of the first and probably the most prominent writer (certainly one of the few in the main stream) in his early years to write for children from an avowedly left-wing stance. And he wrote what was really the first proper survey of children’s literature, Tales Out of School, in 1949. He mainly wrote historical fiction, but other genres too, and died, I think in 1998, at the age of 89, having published well over 100 books. The first volume of his autobiography, A Whiff of Burnt Boats, which covers his childhood and early development as a writer, was republished a few years ago and should still be available, and his best-known book, Cue for Treason, is still in print, as well as several of his other titles. He also wrote for adults, including fiction and plays, as well as “Nottingham – A Biography”, and “Portrait of a Cavalier”, about the first Duke of Newcastle who purchased Nottingham Castle. AS you’ll gather, I’ve been a fan for many years, since I read his books from the library as a child, and huge numbers of children throughout the twentieth century must have been influenced by reading his books. I do hope you’ll agree he is well worth remembering!