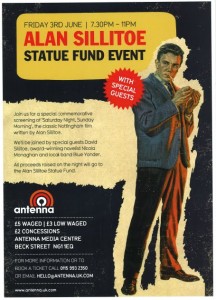

Friday night saw Antenna host their biggest event to date as just over a hundred people came to celebrate the life of Alan Sillitoe. For the fundraising event, we showed Saturday Night and Sunday Morning on an enormous screen, a Q&A with Nicola Monaghan and David Sillitoe and music from Blue Yonder who we’ve shoehorned into events due to their Arthur Seaton-inspired song ‘Propaganda.’ I can’t emphasise how proud it felt to see so many people, particularly given that most would have seen the film countless times before.

Friday night saw Antenna host their biggest event to date as just over a hundred people came to celebrate the life of Alan Sillitoe. For the fundraising event, we showed Saturday Night and Sunday Morning on an enormous screen, a Q&A with Nicola Monaghan and David Sillitoe and music from Blue Yonder who we’ve shoehorned into events due to their Arthur Seaton-inspired song ‘Propaganda.’ I can’t emphasise how proud it felt to see so many people, particularly given that most would have seen the film countless times before.

David Sillitoe is, to quote my girlfriend, ‘a real darling.’ He hasn’t read all of his father’s books (yet) and doesn’t proclaim to offer knowledge on specific literary questions – which must be a little frustrating for the many fans hoping to find those elusive answers yet to be answered in academic journals or newspaper columns, but in this he displays one of his father’s unswerving qualities: unashamed honesty. It also surprised many of the audience that David has never considered writing himself although as Nicola Monaghan observed, ‘my father is an electrician and I’ve never been interested in learning about wires.’

I’ve read Saturday Night and Sunday Morning four times now and seen the film so many times that I know it more or less word for word. It is my version of Star Wars; Sillitoe my Obi Wan, Arthur Seaton my Han Solo. Yet each time the brashness and self-belief of Arthur Seaton never fails to impress me. Seaton is a complex character whose promiscuity is understandably offensive to many women, yet to see him in such one-dimensional terms is to miss the bigger picture and the context of the book. Sex – just as it was for his grandfather, old man Burton (A Man of his Time) – is an escape from the humdrum and drudgery of work and routine. Yes, his actions have consequences and cause harm. But this is the process of life, the learning curve. Wisdom comes from individual mistakes. It doesn’t come through lectures from authority figures. This is the great existential angst of the book, as captured in the fishing metaphor.

“Everyone in the world was caught, somehow, one way or another, and those that weren’t were always on the way to it. As soon as you were born you were captured by fresh air that you screamed against the minute you came out. Then you were roped in by a factory, had a machine slung around your neck, and then you were hooked up by the arse with a wife. Mostly you were like a fish: you swam about with freedom, thinking how good it was to be left alone, doing anything you wanted to do and caring about no-one, when suddenly: SPLUTCH! – the big hook clapped itself into your mouth and you were caught. Without knowing what you were doing you had chewed off more than you could bite and had to stick with the same piece of bait for the rest of your life. It meant death for a fish, but for a man it might not be so bad. Maybe it was only the beginning of something better in life…if you went through life refusing all the bait dangled before you, that would be no life at all. No changes would be made and you would have nothing to fight against.”

Fishing and sex offer Seaton the same thing, a temporary escape, and so feminist readings of the book fail to take into consideration these other, deeper-rooted problems. I mention this as Nicola Monaghan recently gave a talk at Central Library and named SNSM as very influential. This was received with sighs of disapproval by various females in the audience, which Nicola was quite surprised at – and no wonder. In Kerrie-Ann (The Killing Jar) and Frankie Cavanagh (Starfishing) she has created two very strong-willed individuals who take control of their circumstances and take no prisoners. Remind you of anyone..?

For more information on future Sillitoe events see our brand new website. Our next event will hopefully be a showing of The Ragman’s Daughter and some short story readings. But more of this later…