Being banged up in the house for 3 weeks has been tough for many of us, but French philosopher and essayist Michel de Montaigne would have pissed his way through lockdown as he chose to self-isolate for 10 years…

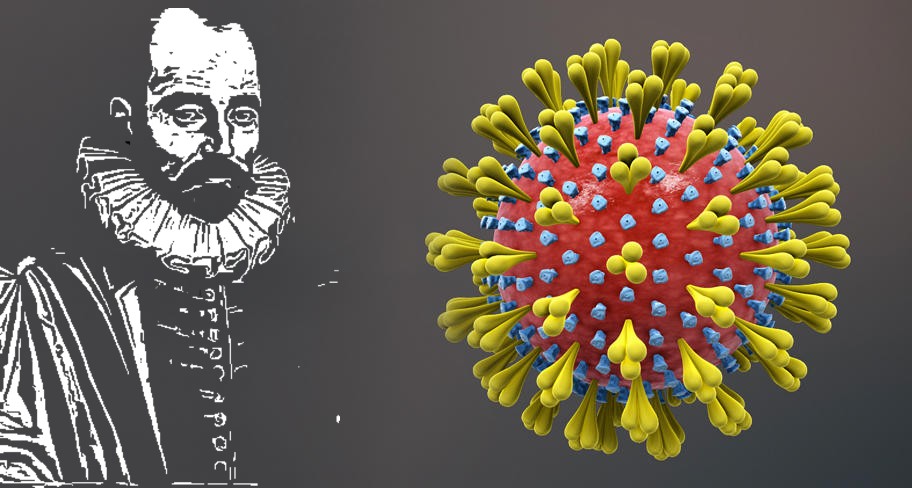

Michel de Montaigne (28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592) was a Renaissance philosopher, statesman and writer best known for making the essay a literary genre. Blending anecdotes about the mundane (he wrote a lot about his aging body) alongside intellectual expositions, he was deemed self-indulgent by his contemporaries. Montaigne is of interest today because he chose to self-isolate for 10 years, which isn’t that surprising when you consider his formative years.

Despite being born into wealth, Montaigne’s father injected a bit of realism into his life early on when he was ushered off to a peasant family for three years to “draw the boy close to the people, and to the life conditions of the people, who need our help”. After this, he was brought back to the family château to learn Latin, spiritual meditation, and be awoken each morning by a servant playing a new instrument. His father was a stickler for rules, putting in place a comprehensive programme for education that would ensure his son craved intellectual liberty as an adult rather than becoming a wealthy layabout. It worked. He became a courtier between 1561 – 1563 and was awarded the collar of the Order of Saint Michael.

Montaigne got married in 1565 and had six daughters, all of whom died, except one. When his father followed suite a few years later, he inherited the family fortune and retired from public life in 1571. Whereas we are obliged to social distance to stop the spread of coronavirus, Montaigne decided to self-isolate to pursue his favourite hobby – himself. To do this, he locked himself away in his library with 1,500 works for company. His isolation would last for nearly ten years, culminating in the publication of three volumes of Essays. To remain motivated, he had inspirational quotes from classical philosophy carved into the wooden beams of the library, as well as his own motivational ponderings:

“In the year of Christ 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, on the last day of February, his birthday, Michael de Montaigne, long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employments, while still entire, retired to the bosom of the learned virgins, where in calm and freedom from all cares he will spend what little remains of his life, now more than half run out. If the fates permit, he will complete this abode, this sweet ancestral retreat; and he has consecrated it to his freedom, tranquility, and leisure.”

Although a vociferous reader, Montaigne was quite happy to give up on a book if it didn’t spark his interest, advising, “I am not prepared to bash my brains for anything…if one book wearies me I take up another.” I guess this isn’t a problem when you’ve got 1,500 to choose from.

Montaigne was not one for reverence. He railed against stuffy academics and pompous intellectuals for whom abstract dogma acted as an intellectual cage that led to hubris, fanaticism and other social nasties. Life, he wrote, “consists partly in madness, partly in wisdom”. Liberty comes from striking a balance between knowledge and pleasure. In modern parlance, he kept it real. Or as he put it, “Kings and philosophers’ shit, and so do ladies.”

Montaigne’s determination to focus on his art is a reminder to all writers that discipline and dedication are equally as important as talent and creativity. It doesn’t matter how great your ideas are if you don’t get them down on paper. It’s in this spirit we should view Lockdown as an opportunity to finish that incomplete novel, now that public distractions are a distant memory.

Of course, it’s easier to write when you’re overlooking the Dordogne from your inherited tower. But writing is magical wherever it happens. It allows temporary escape from our lives as we inhabit other characters and worlds. For Montaigne, writing acted as a form of therapy, an opportunity to escape dark thoughts by getting them down on paper. Writing during Lockdown could be good for our mental health too.

His Essays explore the human condition from various perspectives – fear, happiness, childhood, possessions, fame, with wonderful confessions on the failings of the body – he was as happy writing about poo and impotence as he was a philosophical treatise. Underpinning all of this was gnôti seauton – know thyself.

Coronavirus is forcing us to think about the human condition in terms of poverty, globalisation, pollution, community, health – and how we might live differently when this epidemic passes. Let’s hope our splendid isolation is not for 10 years.

This blog was originally published on the Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature website on 20 April.

I am currently working on Whatever People Say I Am, a graphic novel serial challenging stereotypes, and D.H. Lawrence: A Digital Pilgrimage, a memory theatre exploring Lawrence through artefacts.