Catherine Mumford was born in Ashbourne, Derbyshire on 17 January, 1829 to strict Methodist parents. During childhood she was forbidden from dossing about with other kids for fear that she may ‘catch’ their bad habits. By twelve, she’d read the Bible eight times and given up sugar in protest at the treatment of Negroes. By her late teens she’d joined the Temperance Movement. She would meet her perfect match in William Booth, a man who also excelled in self-denial. Through marriage they made a formidable partnership, sharing an uncompromising set of values that would define the Salvation Army and radically transform the fate of the poor.

As you’d expect from the daughter of an occasional lay preacher, Catherine was a serious and sensitive kid. However it was a spinal problem in 1842 that left her bedridden for months – and would plague her for the rest of her life – that defined her as a person. From her bed she studied theology which would underpin her various moral crusades and lead to her penning some exceptional sermons that would challenge the religious establishment as well as books on Christian living.

She first met William Booth in 1852 at a tea party hosted by Edward Rabbits, a wealthy benefactor who William was trying to tap up. Prior to this both Catherine and William had been visiting the sick in their native Brixton and Nottingham. They were destined for each other. A month later were formally engaged. As their biographer Roy Hattersley notes, ‘In all nineteenth century England there could not have been a couple in which both husband and wife held such strong opinions – and felt such an obligation to impose them on other people.’

William Booth was notoriously averse to reading, seeing theological study as an indulgence that got in the way of proper work. But this didn’t wash with Catherine who accepted no excuses when it came to self-improvement. In one typically condescending letter to William, she put his lack of reading down to poor time management; ‘Could you not rise by six o’clock every morning and convert your bedroom into a study until breakfast time?’

If William was the brawn then Catherine was definitely the brains of the Salvation Army. Her studious nature meant she was able to bring about change through logical and rational enquiry. She was instrumental in creating equality within their ranks by introducing female ministers able to command over men.

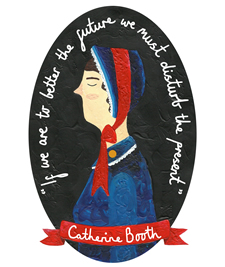

illustration: Lexie Mac in LeftLion.

Unlike her husband, all of Catherine’s beliefs were built on solid fact and biblical exegesis. When William originally opposed women ministers she simply dug deeper for evidence. She eventually found it in St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, Chapter III, Verse 28, which stated: ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bound nor free, there is neither male nor female, for ye are all one in Christ Jesus’.

Catherine published her arguments in various pamphlets and directly challenged religious patriarchy. This was a highly contentious thing to do in 1850s Britain. But the Booths were never ones to worry about public opinion. The only person they were answerable to was Him upstairs.

In stark contrast to William’s histrionics in the pulpit, Catherine’s preaching style, according to the Wesleyan Times, was “no empty boisterousness or violent and cursing declamation, but a calm and simple statement of the unreasonableness of sin.” She brought something different to the table, enabling the Army to diversify its appeal, and it was this that convinced William to embrace spiritual equality.

Catherine’s logical and persuasive arguments were perfect for playing on bourgeois guilt where wasting money on ‘a single bottle of wine for the jovial entertainment of friends’ was an insult to the hardships suffered by the poor. She appealed to their goodwill and conscience, arguing their ‘knowledge of the awful state of things in the world around them must make them fully aware of the good that might be done with the money which they lavish upon their lusts’. Sermons such as this would inspire two wealthy benefactors to donate the costs of hiring their first permanent home in the East End of London.

Preaching brought her into direct contact with deprived communities whose problems were largely caused through alcohol abuse. Catherine started a national campaign raising awareness of the perils of drink and later had abstinence from alcohol written into the Salvation Army’s constitution. She also demanded greater protection for women through the law and recruited women from the working classes, her ‘Hallelujah Lasses’, to support women and children in slum districts. But her crowning glory was getting the age of consent raised from thirteen to sixteen, which helped address child prostitution.

Catherine was against sending children to boarding school on the grounds that their principles were not fully developed and therefore may be more prone to temptation. She believed that it was parents who should provide a Christian upbringing, not headmasters. In her sermons she compared a child brought up without love like a plant without sunlight. However as she was often absent from the home this role often fell to the governess.

Despite her clear love for her eight children, it couldn’t have been much fun for them growing up. They lived a pretty nomadic lifestyle, dragged from town to town, while being subjected to the strictest of rules from their righteous and bigoted parents. The Booths believed that clothing was a form of vanity and so any unnecessary frippery was unstitched before they could wear it. Inevitably their offspring became pious and earnest which led to a fair few kickings in the playground.

The Booths dogmatic regime of constant prayer and absolute discipline meant the children were raised in conditions that make the Taliban look liberal. Sports were banned, they had to take a cold bath everyday – apart from the Sabbath – and their frugal father’s idea of a treat was a scattering of currants on the daily bowl of rice pudding. But only on exceptional occasions.

Matters were made worst by Catherine’s gradual immobility. The birth of eight children had left her an invalid. Although this did not stop her preaching, it had a morbid effect on her moods. During this period melancholy was deemed a disease of the spirit and therefore the ultimate blasphemy as it suggested a denial of God’s love.

In 1887 Catherine was diagnosed with breast cancer but, stoic as ever, refused an operation. As she lay on her deathbed a band was brought into her bedroom, not for personal comfort but so that all of the musicians who she had inspired over the years could show their respects. She was ‘Promoted to Glory’ in 1890 and her body was laid out in Clapton Congress Hall so that 50,000 mourners could visit over five days. A further 36,000 attended her official funeral on 13 October with a procession of 3,000 officers, each wearing white armbands to celebrate her life. And there was plenty to celebrate. She had persuaded William that women were the intellectual and moral equal of men. That it was nurture not nature that held them back and that “if we are to better the future we must disturb the present.” It would take a World War before women won the right to vote in 1918. But it was only in January this year that the Church of England consecrated their first female bishop. Her fight goes on.

The above article was originally published in the Sept 2015 issue of LeftLion magazine as part of the City of Literature series. Two months later Nottingham was accredited as a UNESCO City of Literature. The source for this article is Roy Hattersley’s superb Blood And Fire: William and Catherine Booth and the Salvation Army. The video was created by Josh Dunne, a 2nd year media student from Nottingham Trent University as part of a placement scheme with Dawn of the Unread.