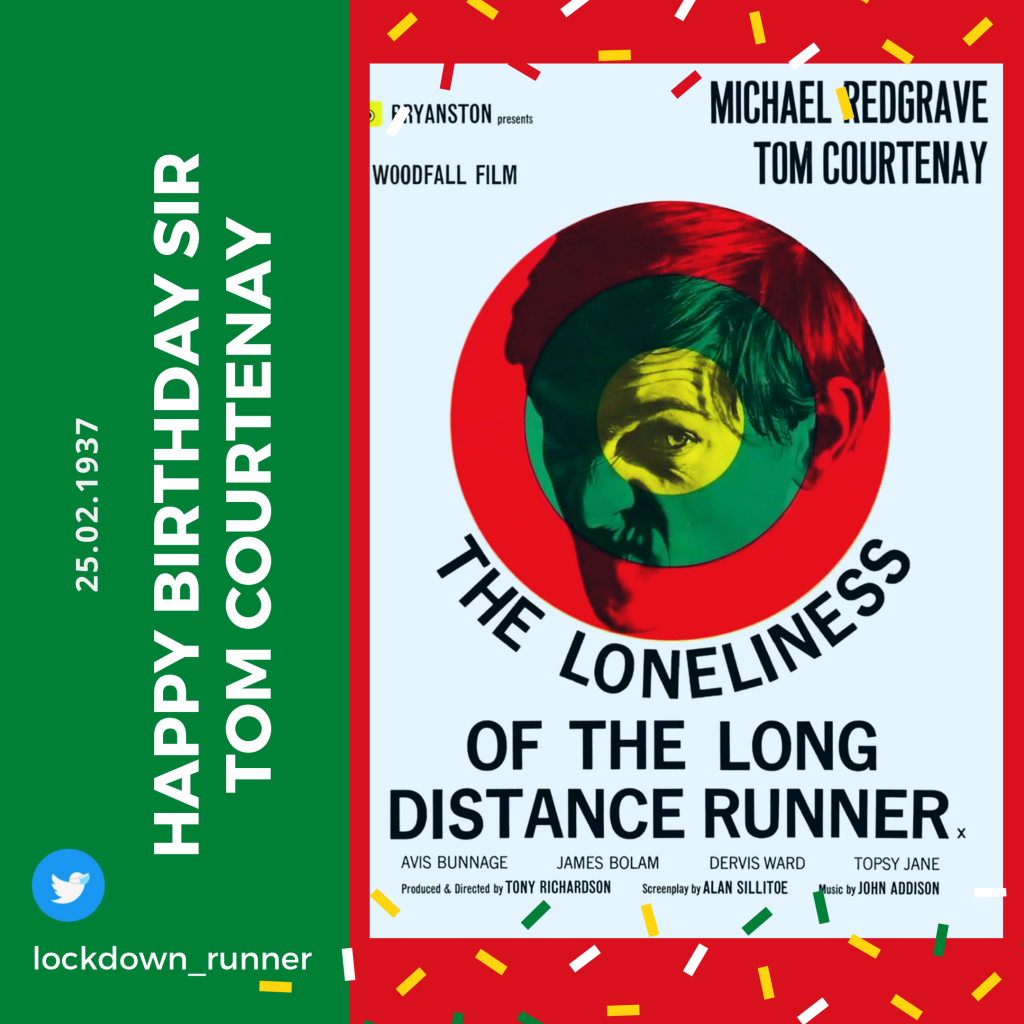

To mark the 84th birthday of Sir Tom Courtenay, who played Colin Smith in the film adaptation of Sillitoe’s 1959 short story The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, I’ve updated the tale for the lockdown generation. This first of two blogs explains why.

During Lockdown, we’ve all found inventive ways of coping with our enforced solitude. From baking bread to learning a language, we’ve all experimented with different forms of distraction, now the pubs and restaurants are closed. But one trend that seems to be growing in popularity is the lockdown runner, or, more specifically, lumbering overweight middle-aged men.

Amid a pandemic that requires us to keep a reasonable distance from each other and to be hyper conscious of our hygiene, joggers seem to think now is the time to come panting and spluttering past like a back firing Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Worst still, you can’t even tell them to back off as they’re tethered to their headphones.

I should point out that I, too, am an overweight middle-aged man. I’m just too lazy to plod and pant my way across the streets. I prefer to saunter so that I connect with my immediate environment and count how many discarded face masks are on our street.

All of this got me thinking about Alan Sillitoe’s 1959 short story ‘The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner’. In this, seventeen-year-old Colin Smith is sent to Borstal for robbery. The governor notices he is a talented runner and puts him forward for a national long-distance running competition. Smith is athletic because ‘running had always been made much of in our family, especially running away from the police’. If he wins the race, as the governor is counting on him to do, it will vindicate the very system and society that has locked him up. It is a superb story of defiance and belligerence, casting Colin Smith as one of the greatest literary anti-hero’s of all time.

Picture from Dawn of the Unread.

In ‘For it was Saturday Night,’ one of the comics in the Dawn of the Unread series, I brough Colin Smith back from the dead to fight against the closure of libraries. But due to rigor mortis, he was so slow he didn’t get very far. Now I’m adapting the story once more, but this time for the covid generation in ‘The Loneliness of the Lockdown Runner’

This will be published as 100 tweets on Twitter at 5pm for five evenings, starting on Thursday 25 Feb. This is to mark the 84th birthday of Sir Tom Courtenay, who played Colin Smith in the British New Wave film of 1962.

The story will incorporate large chunks of text from the original story but with a lockdown twist. Our homes have now become mini Borstals and the governor is Boris Johnson and the Tory party, imparting wisdom and enforcing restrictions while flouting the rules themselves. As Sillitoe may have wrote:

“For when the governor talked to me of being honest, he didn’t know what the word meant, or he wouldn’t have had me locked up indoors while he went trotting along in sunshine to Bernard Castle.”

I’ve decided to reimagine the story on Twitter because, like Lockdown, Twitter is a medium of constraint. It also means I can attach links to covid related articles to document the epidemic. Similarly, the story can be told in short, sharp bursts, replicating the slow-paced trot of lockdown running. I like the idea of the form reflecting the content.

David Mitchell is largely credited as writing the first ‘official’ short story for Twitter for ‘The Right Sort’ (2014). He was drawn by the challenges ‘posed by diabolical treble-strapped textual straightjackets’. I have a far simpler objective; drawing attention to one of the greatest short stories ever written, and, like the bread bakers and lumbering joggers, keeping myself occupied during lockdown.

Follow @Lockdown_Runner

Related articles

- Twitter @Lockdown_Runner (twitter.com/Lockdown_Runner)

- Twitterature: Lockdown Runner Tweets (jameskwalker.co.uk)

- Happy Birthday Sr Tom, here’s your prezzie (dawnoftheunread.wordpress.com)

- Reimagining Sillitoe during covid (leftlion.co.uk)

- Loneliness of the Lockdown Runner (nottinghamcityofliterature.com)

- Twitterature: The Loneliness of the Lockdown Runner (jameskwalker.co.uk)

- Twitterature: Reimagining Sillitoe’s class for the covid generation (jameskwalker.co.uk)

- For it was Saturday Night (dawnoftheunread.com)